ORIGINAL

Family Funcionality in Women Victims of Family Violence in time of COVID-19 in Areas of Lima

Funcionalidad familiar en mujeres víctimas de violencia familiar en tiempos de COVID-19 en zonas de Lima

Lucia Asencios-Trujillo1 ![]() *, Lida Asencios-Trujillo1

*, Lida Asencios-Trujillo1 ![]() *, Carlos La Rosa-Longobardi1

*, Carlos La Rosa-Longobardi1 ![]() *, Djamila Gallegos-Espinoza1

*, Djamila Gallegos-Espinoza1 ![]() *, Livia Piñas-Rivera1

*, Livia Piñas-Rivera1 ![]() *, Rosa Perez-Siguas2

*, Rosa Perez-Siguas2 ![]() *

*

1Universidad Nacional de Educación Enrique Guzmán y Valle, Escuela de Posgrado. Lima, Perú.

2Instituto Peruano de Salud Familiar, TIC Research Center: eHealth & eEducation. Lima, Perú.

Cite as: Asencios-Trujillo L, Asencios-Trujillo L, La Rosa-Longobardi C, Gallegos-Espinoza D, Piñas-Rivera L, Perez-Siguas R. Family Funcionality in Women Victims of Family Violence in time of COVID-19 in Areas of Lima. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:775 https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024775

Submitted: 21-10-2023 Revised: 22-12-2023 Accepted: 13-02-2023 Published: 14-02-2023

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: during confinement many of the families have foreseen a situation that compromises the relationship of their members, where communication within the home will play an important role in the emotional balance in the family, to the objective of the study is to determine the family functionality in women victims of family violence in times of COVID-19 in areas of Lima.

Methods: it is a is quantitative, its methodology is descriptive, not experimental, cross-sectional, with a total population is made up of 794 women participants from areas of Lima, who answered a questionnaire on sociodemographic aspects and the scale FACES IV.

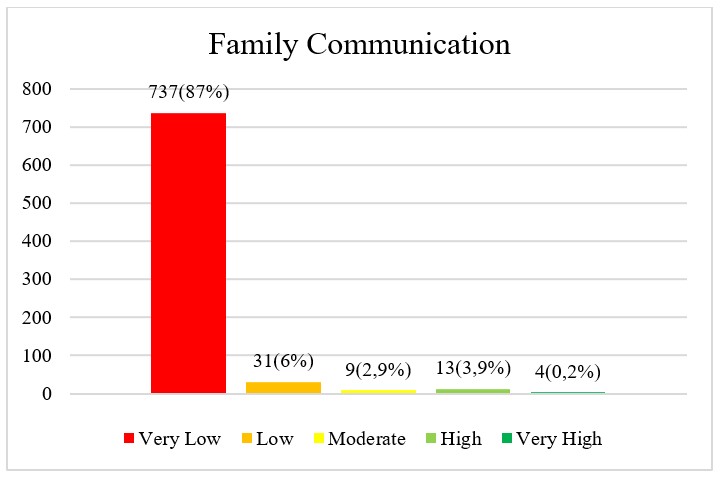

Results: in the results we can observe in the dimension family communication that, 737 (87 %) of the women victims of family violence have very low communication with the other family members, 31 (6 %) have a low family communication, 9 (2,9 %) have a moderate family communication, 13 (3,9 %) have a high family communication and 4 (0,2 %) have very high family communication.

Conclusions: it is concluded that health services should be taken into account, where health professionals can identify situations of risk of violence within the home and that can prevent it.

Keywords: Mental Health; Domestic Violence; Pandemic; Coronavirus.

RESUMEN

Introducción: durante el encierro muchas de las familias han previsto una situación que compromete la relación de sus miembros, donde la comunicación dentro del hogar jugará un papel importante en el equilibrio emocional en la familia, al objetivo del estudio es determinar la funcionalidad familiar en mujeres víctimas de violencia familiar en tiempos de COVID-19 en zonas de Lima.

Métodos: Es un es cuantitativo, su metodología es descriptiva, no experimental, transversal, con una población total está conformada por 794 mujeres participantes de zonas de Lima, quienes respondieron un cuestionario sobre aspectos sociodemográficos y la escala FACES IV.

Resultados: En los resultados podemos observar en la dimensión comunicación familiar que, 737 (87 %) de las mujeres víctimas de violencia familiar tienen una comunicación muy baja con los demás miembros de la familia, 31 (6 %) tienen una comunicación familiar baja, 9 (2,9 %) tienen una comunicación familiar moderada, 13 (3,9 %) tienen una comunicación familiar alta y 4 (0,2 %) tienen una comunicación familiar muy alta.

Conclusiones: Se concluye que se deben tener en cuenta los servicios sanitarios, donde los profesionales de la salud pueden identificar situaciones de riesgo de violencia dentro del hogar y que pueden prevenirla.

Palabras clave: Salud Mental; Violencia Intrafamiliar; Pandemia; Coronavirus.

INTRODUCTION

At the international level, as the lockdowns due to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID – 19) are reduced, as a result, it has been expected that during those months, domestic and gender violence has increased considerably in the world population, but that the highest peaks occurred more during this pandemic period of COVID – 19.(1,2)

Likewise, as the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic intensifies in the country, many of its effects on mental health in people have been called attention, which has generated an increase in violence against women by their partner during the outbreak and quarantine by COVID-19,(3) Therefore, these prevention measures have had a great impact on family dynamics, having an effect on family income, interpersonal income, well-being and mental health.(4,5)

In such a way that family support to cope with this COVID-19 crisis is not adequate, because the family structure in times of pandemic has been diminished due to factors such as personal and social stress(6) since this generates a great impact on families where fear and uncertainty due to COVID-19 will trigger various forms of intra-family conflicts.(7,8)

While it is true that social distancing and quarantine of the population will reduce the spread of COVID-19, but that this exposes dysfunctional families on a physical, emotional and economic level, related to domestic violence that could cause permanent injuries or the death of the victim and their descendants,(9,10) and that the increase in domestic violence will extend for a time when a natural disaster that lasts for 11 months reverberates.(11)

In a study conducted in Nigeria [12intimate partner violence increased considerably in dysfunctional families and that they involved new types of violence during the COVID-19 lockdown, and that the cases occurred more physical, economic, psychological and sexual violence, and that it was also related to the economic stressors associated with COVID-19.

In a study conducted in Iran(13) it was observed in 250 pregnant participants, that 35,2 % of them have suffered domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, among them emotional violence (32 %), sexual violence (12,4 %) and physical violence (4,8 %).

In a study conducted in Ecuador(14) they argued that domestic violence increased during isolation and that unemployment, economic stress and confinement highlighted the tension caused by violence by their partner.

Therefore, the research objective is to determine the family functionality in women victims of family violence in times of COVID-19 in areas of Lima.

Thus, as a justification for the research, determining family functionality in victims of family violence during the pandemic not only helps us to understand this problem in depth, but also supports us as a basis for the design of different effective interventions aimed at protecting the well-being of each woman in times of crisis worldwide.

METHODS

Type of Research

The research for its properties is quantitative, its methodology is descriptive, not experimental, cross-sectional.(15)

Population

The total population is made up of 794 women participants from areas of Lima

Inclusion criteria

· Women residing more than 3 years in the same locality

· Women who voluntarily participate in the study

· Women who have signed the informed consent

· People who signed the inform consent CIE IPSF 018-2023. It was previously accepted by the institution.

Technique and Instrument

The technique for the study is carried out using the questionnaire or data collection instrument FACES IV, which aims to measure family functionality in women victims of family violence in times of COVID-19 in areas of Lima.

Olson's FACES IV scale: consisting of 62 items. The dimensions of family cohesion and family flexibility use six scales (Balanced Cohesion, Balanced Flexibility, Tangled, Disconnected, Rigid and Chaotic). There are two balanced scales that assess balanced family cohesion and family flexibility. In addition, there are two unbalanced scales for cohesion which are detached and entangled. And two unbalanced scales for flexibility that are rigid and chaotic. In addition, FACES IV evaluates communication and family satisfaction. Each scale is composed of seven items; forming a total of 42 items, which is scored through a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), and can be answered by people over 12 years old. The FACES IV additionally has 20 more items, 10 of them evaluate family communication and the remaining 10 family satisfaction. Each balanced scale has three final values ranging from something connected, connected, and highly connected for the balanced cohesion scale to something flexible, flexible, and very flexible for the balanced flexibility scale. Each unbalanced scale consists of 5 final values ranging from the very low, low, moderate, high, and very high values. Finally, the variable Family dynamics or general family functionality has 3 final values that are balanced families, families with average rank and unbalanced families. This final assessment may be modified, depending on how family dynamics vary.(16)

Instrument location and application

The survey carried out to measure the functionality of women victims of family violence was carried out in different districts of Lima such as Puente Piedra, Carabayllo, Comas, Los Olivos, San Martin de Porres, Independencia, Breña, Santa Luzmila.

To start the data collection, coordination is made with each female member of the household, in order to carry out the research work, and in turn provide and detail about the study, so that they have knowledge about what they are going to do during the completion of the survey.

RESULTS

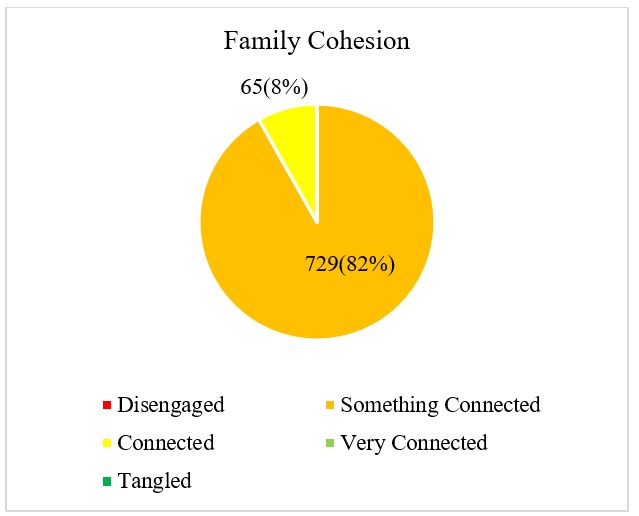

Figure 1. Family Functionality in its dimension Family Cohesion in women victims of family violence in times of COVID-19 in areas of Lima

In figure 1, we can see in the dimension family cohesion that, 729 (82 %) women victims of family violence are somewhat connected with other family members and 65 (8 %) of women if they are connected with family members.

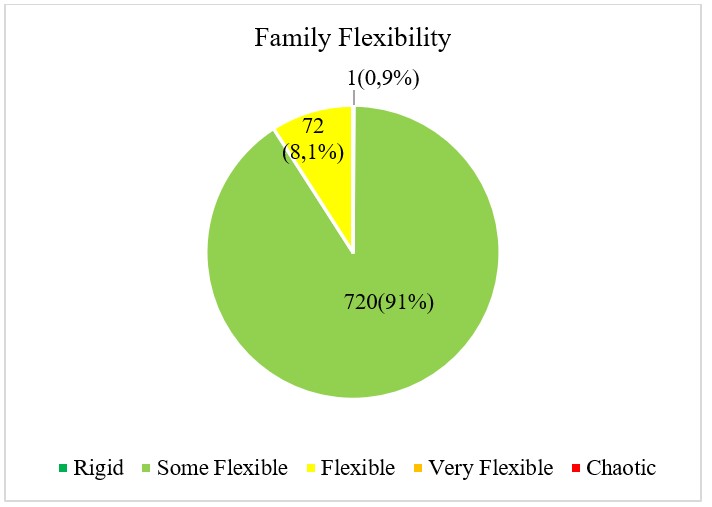

Figure 2. Family Functionality in its dimension Family flexibility in women victims of family violence in times of COVID-19 in areas of Lima

In figure 2, we can see in the family flexibility dimension that, 1 (0,9 %) of women victims of family violence are rigid with other family members, 720 (91 %) of women are somewhat flexible with other family members and 72 (8,1 %) of women are flexible with other family members.

Figure 3. Family Functionality in its dimension Family communication in women victims of family violence in times of COVID-19 in areas of Lima

In figure 3, we can see in the family communication dimension that 737 (87 %) of women victims of family violence have very low communication with other family members, 31 (6 %) have low family communication, 9 (2,9 %) have moderate family communication, 13 (3,9 %) have high family communication and 4 (0,2 %) have very high family communication.

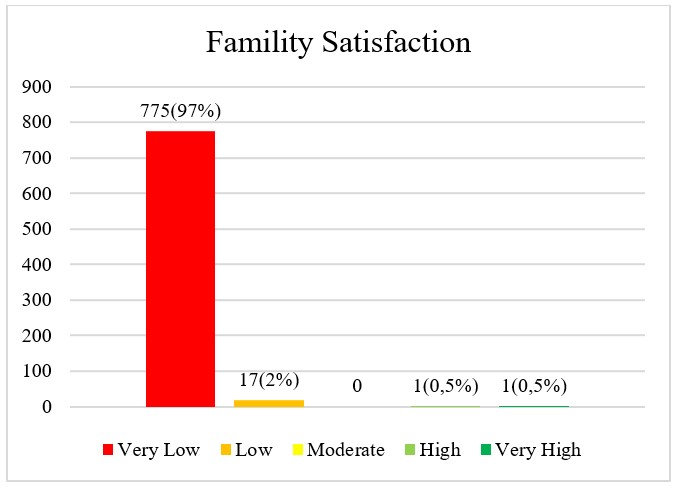

Figure 4. Family Functionality in its dimension Family satisfaction in women victims of family violence in times of COVID-19 in areas of Lima

In figure 4, we can see in the dimension family satisfaction that, 775 (97 %) of women victims of family violence have a very low family satisfaction, 17 (2 %) have low family satisfaction, 1 (0,5 %) have high family satisfaction and 1 (0,5 %) have very high family satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

In the present research work is given from the point of view of family and mental health in women victims of family violence in relation to family functionality.

In the results we observe that women victims of family violence have a very low family functionality with respect to their dimensions, this is due to the fact that since the confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in several households they have had the opportunity to interact with other family members but that sometimes in some families because of COVID-19 and confinement has only generated violence at home Especially violence by the male towards his partner, this is due to unemployment, stress crises within the home and the new rules inside and outside the home, has generated more violence within the home. The authors explicitly mention that if the current trajectory of COVID-19 induced confinement persists, domestic violence cases (most pronounced within intimate partners) will witness an even more distressing escalation. This grim anticipation paints a sobering picture of the pandemic's deep social ripples, reverberating within the family unit itself.(3) Other authors mention that violence within the home towards women is due to an accumulation of tension on the part of the couple, an emerging perspective underscores that the accumulation of tensions within a society, often exacerbated by financial constraints stemming from inadequate income, can catalyze the emergence of negative emotions. These emotions, ranging from verbal insults and explosive shouting fights to full-blown arguments, merge to create a volatile emotional landscape, ripe for the eventual eruption of violent behaviors. This unfortunate pattern of behavior is a manifestation of deep-seated socioeconomic stressors that have only intensified in the context of the current pandemic, further underscoring the urgency of addressing the multifaceted challenges faced by struggling families.(13)

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that prevention strategies against violence should be sought during and after the COVID-19 pandemic and disseminate information so that the majority of the population can be educated.

It is concluded that the population should be made aware of the prevention of violence within the home, whether in social networks, in the community, advertisements, which guide the population on how to prevent violence

It is concluded that health services should be taken into account, where health professionals can identify situations of risk of violence within the home and that can prevent it.

Given the complexity and implication of the study, it is important to take into account the challenges that women have to face in situations of violence, as this negatively impacts their mental and emotional well-being, certain implications such as the cycle of violence and mental health, the effects of quality of life and the needs of some psychosocial support, They are those that have to take into account in order to contribute to a policy or program in a solid way, address violence against women and what consequences may affect it.

The limitation in our study is the access to the homes of each of the participants, since many times we found it with the head of the family who did not agree that his life partner would participate, in addition to the fact that the same study population did not want to be present in the study.

REFERENCES

1. Fernandes C, Magalhães B, Silva S, Edra B. Perception of family functionality during social confinement by Coronavirus Disease 2019. Journal of Nursing and Health 2020;10:1–14. https://doi.org/10.15210/jonah.v10i4.19773.

2. Sri A, Das P, Gnanapragasam S, Persaud A. COVID-19 and the violence against women and girls: ‘The shadow pandemic.’ International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2021;1:17–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764021995556.

3. Sánchez O, Vale D, Rodrigues L, Surita F. Violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2020;151:180–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13365.

4. Lorente M. Violencia de género en tiempos de pandemia y confinamiento. Revista Española de Medicina Legal 2020;46:139–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2020.05.005.

5. Kalokhe A, del Rio C, Dunkle K, Stephenson R, Metheny N, Paranjape A, et al. Domestic violence against women in India: A systematic review of a decade of quantitative studies. Global Public Health 2017;12:498–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1119293.

6. Evans M, Lindauer M, Farrell M. A Pandemic within a Pandemic — Intimate Partner Violence during Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;383:2302–4. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2024046.

7. Guerrero D, Salazar D, Constain V, Perez A, Pineda C, García H. Association between Family Functionality and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Korean Journal of Family Medicine 2021;42:172–80. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.19.0166.

8. Usher K, Bhullar N, Durkin J, Gyamfi N, Jackson D. Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 2020;29:549–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12735.

9. Telles L, Valença A, Barros A, da Silva A. Domestic violence in the COVID-19 pandemic: a forensic psychiatric perspective. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 2020;0:5–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1060.

10. Gonzalez-Argote J. A Bibliometric Analysis of the Studies in Modeling and Simulation: Insights from Scopus. Gamification and Augmented Reality 2023;1:5–5. https://doi.org/10.56294/gr20235.

11. Rodríguez FAR, Flores LG, Vitón-Castillo AA. Artificial intelligence and machine learning: present and future applications in health sciences. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education 2022;1:9-9. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw20229.

12. Aveiro-Róbalo TR, Pérez-Del-Vallín V. Gamification for well-being: applications for health and fitness. Gamification and Augmented Reality 2023;1:16–16. https://doi.org/10.56294/gr202316.

13. Inastrilla CRA. Data Visualization in the Information Society. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education 2023;2:25-25. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw202325.

14. Barrios CJC, Hereñú MP, Francisco SM. Augmented reality for surgical skills training, update on the topic. Gamification and Augmented Reality 2023;1:8–8. https://doi.org/10.56294/gr20238.

15. Abdullah M, Jassim H. ASSESSMENT OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN. Journal of Critical Reviews 2020;7:2446–50.

16. Krishnakumar A, Verma S. Understanding Domestic Violence in India During COVID-19: a Routine Activity Approach. Asian Journal of Criminology 2021;16:19–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09340-1.

17. Fawole O, Okedare O, Reed E. Home was not a safe haven: women’s experiences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria. BMC Women’s Health 2021;21:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01177-9.

18. Naghizadeh S, Mirghafourvand M, Mohammadirad R. Domestic violence and its relationship with quality of life in pregnant women during the outbreak of COVID-19 disease. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2021;21:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03579-x.

19. Herrera B, Cardenas B, Tapia J, Calderon K. Violencia intrafamiliar en tiempos de Covid-19 : Una mirada actual Intrafamily violence in times of Covid-19 : A current look Violência intrafamiliar em tempos de Covid-19 : um olhar atual. Polo Del Conocimiento 2021;6:1–13. https://doi.org/10.23857/pc.v6i2.2334.

20. Fernández C, Baptista P. Metodología de la Investigación. 6ta ed. México: Mc Graw-Hill/Interamericana. 2015.

21. Olson D. FACES IV and the Circumplex Model: Validation Study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 2011;37:64–8.

FINANCING

The authors did not receive financing for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo, Lida Asencios-Trujillo, Carlos La Rosa-Longobardi, Djamila Gallegos-Espinoza, Livia Piñas-Rivera, Rosa Perez-Siguas.

Data curation: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo, Lida Asencios-Trujillo.

Formal analysis: Lida Asencios-Trujillo.

Acquisition of funds: Djamila Gallegos-Espinoza, Livia Piñas-Rivera.

Research: Rosa Perez-Siguas, Lucia Asencios-Trujillo, Lida Asencios-Trujillo.

Methodology: Lida Asencios-Trujillo.

Project management: Djamila Gallegos-Espinoza, Livia Piñas-Rivera.

Resources: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo, Lida Asencios-Trujillo.

Software: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo, Lida Asencios-Trujillo.

Supervision: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo, Lida Asencios-Trujillo.

Validation: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo, Lida Asencios-Trujillo, Carlos La Rosa-Longobardi.

Display: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo.

Drafting - original draft: Djamila Gallegos-Espinoza, Livia Piñas-Rivera.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Lucia Asencios-Trujillo.