ORIGINAL

Intervention of Nursing in the Family Functionality of Women Victims of Family Violence in an Area of Lima

Intervención de Enfermería en la Funcionalidad Familiar de Mujeres Víctimas de Violencia Familiar en una Zona de Lima

Rosa Perez-Siguas1 *,

Hernan Matta-Solis1 *, Eduardo Matta-Solis1

*, Luis Perez-Siguas1

*, Victoria

Tacas-Yarcuri1 *,

Hernan Matta-Perez1 *, Alejandro

Cruzata-Martinez1 *,

Brian Meneses-Claudio2 ![]() *

*

1TIC Research Center: eHealth & eEducation, Instituto Peruano de Saud Familiar. Lima, Perú.

2Universidad Tecnológica del Perú. Perú.

Cite as: Perez-Siguas R, Matta- Solis H, Matta- Solis E, Perez-Siguas L, Tacas-Yarcuri V, Matta-Perez H, Cruzata-Martinez A, Meneses-Claudio B. Intervention of Nursing in the Family Functionality of Women Victims of Family Violence in an Area of Lima. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:784. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024784

Submitted: 30-11-2023 Revised: 06-01-2024 Accepted: 15-02-2024 Published: 16-02-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

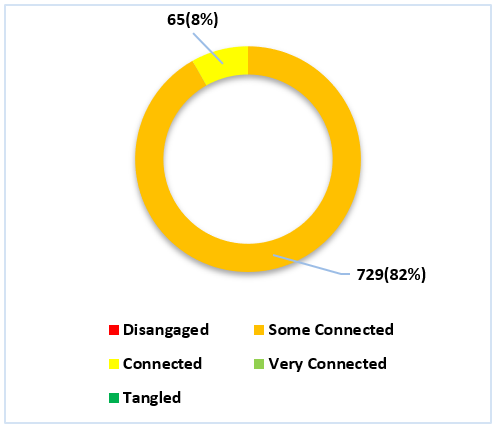

Violence against women is any public health problem since it takes many forms in which the couple exercises power and control over it in a violent way, so the research objective is to determine the intervention of nursing in the family functionality of women victims of family violence in an area of Lima. It is a quantitative-descriptive, cross-sectional study, with a total population of 794 women, who answered a questionnaire on sociodemographic aspects and the Faces IV instrument. In the results, 729 (82 %) women have somewhat connected family functionality and 65(8 %) a connected family functionality. In conclusion, home visits by health professionals should be taken into account for the early detection of risk factors that resemble violence against women in the home.

Keywords: Mental Health; Domestic Violence; Family Functionality.

RESUMEN

La violencia contra la mujer es todo problema de salud pública ya que adopta múltiples formas en las que la pareja ejerce poder y control sobre ella de manera violenta, por lo que el objetivo de la investigación es determinar la intervención de enfermería en la funcionalidad familiar de mujeres víctimas de violencia familiar en una zona de Lima. Se trata de un estudio cuantitativo-descriptivo, de corte transversal, con una población total de 794 mujeres, quienes respondieron un cuestionario sobre aspectos sociodemográficos y el instrumento Faces IV. En los resultados, 729 (82 %) mujeres tienen funcionalidad familiar algo conectada y 65(8 %) una funcionalidad familiar conectada. En conclusión, las visitas domiciliarias de los profesionales de la salud deberían tenerse en cuenta para la detección precoz de los factores de riesgo que se asemejan a la violencia contra la mujer en el hogar.

Palabras clave: Salud Mental; Violencia Doméstica; Funcionalidad Familiar.

INTRODUCTION

The health of the family goes beyond the physical and mental conditions of its members; in which it provides a social environment for the natural development and personal fulfillment of all who are part of it”. It defines violence as: “The intentional use of force or physical power, in fact or as a threat, against oneself, another person, or a group or community, which causes or is likely to cause injury, death, psychological harm, developmental disorders or deprivation. Being one of the most common forms of violence against women is that inflicted by their husband or male partner”.(1)

According to the United Nations (UN) determines that “family violence” is defined as a pattern of behavior used in any relationship to obtain or maintain control over the couple, constituting abuse any physical, sexual, emotional, economic or psychological act that influences another person,(2) in turn in the National Assembly of the United Nations, the family was considered as the natural and fundamental unit of society, with the right to the protection of its integrity by society and the State.(3) Since it is a social phenomenon that takes place inside homes, in which the victims, in most cases are women. However, it also affects children, adolescents, older adults in their physical, patrimonial, psychological, emotional and sexual integrity.(4)

Globally, the interaction of situational stressors related to the pandemic and measures implemented to reduce the community spread of COVID-19 have created new opportunities for violence against women, so much so that increased responsibilities, financial stress, job insecurity, social isolation and inefficiency of support services have increased the risk of violence in the domestic environment.(5,6)

At present, domestic violence has become a serious public health problem with very negative consequences for all members of the family and society as a whole, being considered a serious obstacle to development and peace.(7) Violence against women therefore causes serious short- and long-term physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health problems; The consequences also affect their children and generate a high social and economic cost for women, their families and society.(8,9)

In North America, a study in Cuba of 378 women revealed that the types of violence reported by the women studied predominated physical violence in 18 (41,9 %) and the figure of the family nucleus perpetrator of violence and the husband or partner heads the group (44,2 %). 41,9 % who were physically abused recognized it and 53,5 % who were victims of other types of violence, do not perceive them.(10) Another study conducted in the city of Acapulco in Mexico to 158 women revealing that 73,5 % lived in a dysfunctional family, finding a significant association between suffering violence and living within a dysfunctional family, finding that 30,4 % have suffered psychological violence, 7,6 % suffered physical violence.(11)

In Europe, a study in Australia of 1500 women by the Australian Institute of Criminology found that in the first 3 months of government-mandated confinement, it revealed that 53,1 % said that violence within the family nucleus had increased in frequency or severity and that the most common forms of violence were physical in 71,7 % and sexual violence in 47,1 %. Showing that family violence where women were affected correlates with the aggressor, who is mostly the spouse.(12)

In Asia, a study conducted in China of 813 women revealed that 15,6 % suffered from some form of violence in at least one form, 11,7 % suffered from mental violence, followed by physical violence with 0,9 % and sexual violence with 0,6 %; and 5,4 % reported that they were afraid of the person who hurt them. Suggesting that poor family function is a risk factor for domestic violence.(13) Another study in India of 94 victims of domestic violence, where 58,5 % were women, revealed that 8,5 % suffered domestic violence in the last year, in which verbal abuse is 62,5 %. 7,4 % suffered domestic violence during confinement, while 85,7 % reported an increase in the frequency of violence during the confinement period, evidencing that poor functionality is a consequence of domestic violence.(14)

In South America, a study of northern Colombia has presented 5,937 cases of violence against women; Of these, 5 % correspond to cases of violence against girls and adolescents, 1 % violence against women belonging to the elderly, 79 % represented in violence against the couple and 15 % among other relatives, revealing that in families there are disputes caused preferably by economic situations (19 %), jealousy (24 %) and alcohol consumption (11 %), detailing that poor functionality due to disputes mostly causes domestic violence.(15) Another study conducted in Peru of 250 abused women revealed that 50,8 % were victims of physical violence at some time in the 7,6 % in the last year; 68,4 % were victims of psychological violence and 8,8 % were victims of sexual violence. It was evident that women with psychological violence were those belonging to the single-parent family and women with moderate to severe functionality presented a higher percentage of psychological violence. However, women who experienced sexual violence were reported in women with severe family functionality.(16)

Therefore, the objective of the research is to determine the nursing intervention in the family functionality of women victims of family violence in an area of Lima.

METHODS

Research type and Design

According to the properties of the present research is quantitative, descriptive-transversal methodology.(17)

Population

The total population is made up of a total of 794 female participants.

Inclusion Criteria

· Participants who are over 18 years old

· Female participants

· Participants who voluntarily participate in the study

Technique and Instrument

The data collection technique was the survey, in which sociodemographic data and the FACES IV instrument are found.

Olson's FACES IV Scale consists of 62 items distributed in two dimensions (family cohesion and family flexibility) of which they present 6 scales (Balanced cohesion, Balanced flexibility, Tangled, Disconnected, Rigid and Chaotic). There are two balanced scales that assess balanced family cohesion and family flexibility. In addition, there are two unbalanced scales for cohesion which are detached and entangled. And two unbalanced scales for flexibility that are rigid and chaotic. In addition, FACES IV evaluates communication and family satisfaction. Each scale is composed of seven items; forming a total of 42 items, which is scored through a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), and can be answered by people over 12 years old. The FACES IV additionally has 20 more items, 10 of them evaluate family communication and the remaining 10 family satisfaction. Each balanced scale has three final values ranging from something connected, connected, and highly connected for the balanced cohesion scale to something flexible, flexible, and very flexible for the balanced flexibility scale. Each unbalanced scale consists of 5 final values ranging from the very low, low, moderate, high, and very high values. Finally, the variable Family dynamics or general family functionality has 3 final values that are balanced families, families with average rank and unbalanced families. This final assessment may be modified, depending on how family dynamics vary.(18)

Place and Application of the Instrument

For the collection of data through the survey, coordination was made with the members of the female household of different districts of Lima, in which detailed information about the study was provided and in turn they have the knowledge of what is going to be carried out.

RESULTS

Figure 1. Family functionality in its family cohesion dimension

In figure 1, it can be seen that 82 % (n=729) of the participants have a somewhat connected family functionality according to their dimension family cohesion and 8 % (n=65) are with a connected family functionality.

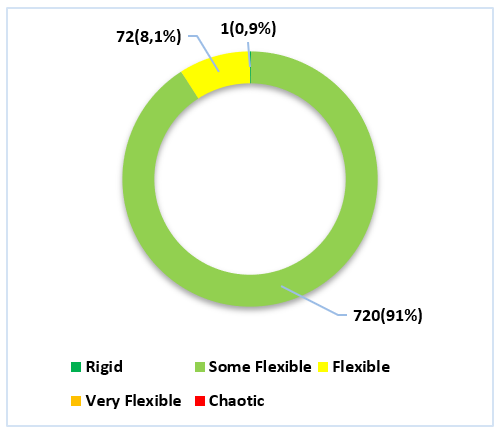

Figure 2. Family functionality in its dimension family flexibility

In figure 2, as can be seen, 91 % (n=720) of the participants have a somewhat flexible family function according to their family flexibility dimension, 8,1 % (n=72) have a flexible family functionality and 0,9 % (n=1) have a rigid family function.

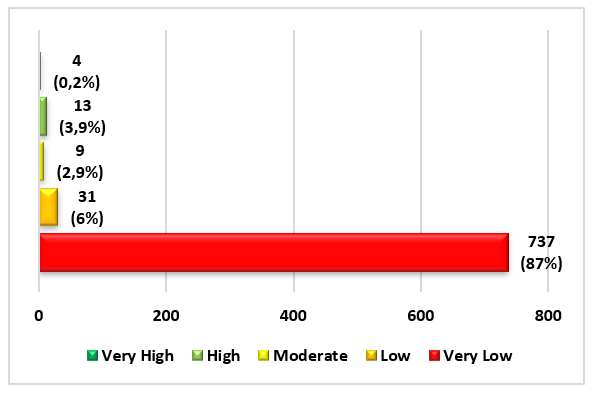

Figure 3. Family functionality in its family communication dimension

In figure 3, as can be seen, 875 (n = 737) of the participants have very low family functionality in terms of their family communication dimension, 6 % (n = 31) have low functionality, 2,9 % (n = 9) have moderate family functionality, 3,9 % (n = 13) have high family functionality and 0,2 % (n = 4) have very high family functionality.

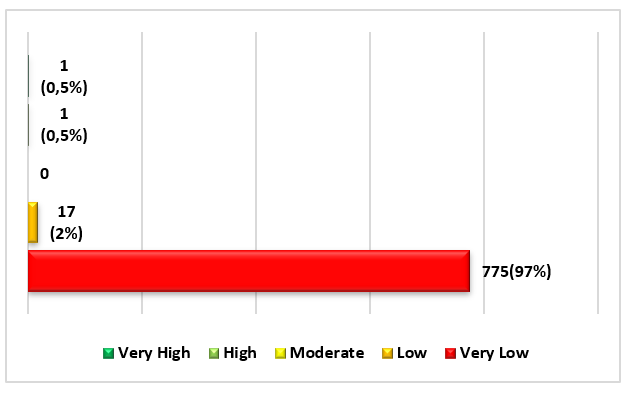

Figure 4. Family functionality in its family satisfaction dimension

In figure 4 we can see that 97 % (n=775) of the participants have a very low functionality with respect to their family satisfaction dimension, 2 % (n=17) have a low functionality, 0,5 % (n=1) a high family functionality and 0,5 % (n=1) a very high family functionality.

DISCUSSIONS

In the present research work is based on the mental health and family health that occurs in women who are victims of violence within the home relating it to their family functionality.

It can be observed in their results that the family functionality in women victims of violence is little, this is because, in several homes, the opportunity to interact with other family members is conflictive, highlighting the family dysfunction that lies within the home, allowing family members who come to visit to realize that within their home the environment is violent; since before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence has always been present especially by men towards women, where physical and psychological aggression generates mental disorders that cause depression, post-traumatic stress, insomnia, eating disorders, emotional suffering and even suicide of women. But that not only affects the couple product of family dysfunction within the home, but the most affected are the children who, seeing any act of violence against the mother, generate factors such as fear when approaching the father, being afraid of any adult or doing violence within the school, all this shows that, In the son's family there is violence.

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that counseling should be sought on how to prevent domestic violence and disseminate information so that the population can have that knowledge and be able to do it

It is concluded that home visits should be made by health professionals, to observe and identify risk factors that seem that women are suffering acts of violence and how to prevent them.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization, "Violence and Mental Health," 2012. Accessed: Dec. 04, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.uv.mx/psicologia/files/2014/11/Violencia-y-Salud-Mental-OMS.pdf.

2. United Nations, "What is Domestic Abuse?," UN, 2021. https://www.un.org/es/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse (accessed Dec. 04, 2022).

3. United Nations, "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights," UN, 2021. https://www.un.org/es/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed Dec. 04, 2022).

4. M. Sánchez, "Violencia familiar: legislación nacional y políticas públicas," Direccion General de Analisis Legislativo. pp. 1–24, 2021, [Online]. Available: http://bibliodigital.senado.gob.mx.

5. A. Peterman et al. , "Pandemics and Violence Against Women and Children," 2020. [Online]. Available: www.cgdev.org.

6. A. Krishnakumar and S. Verma, "Understanding Domestic Violence in India During COVID-19: a Routine Activity Approach," Asian J. Criminol. , vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 19–35, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11417-020-09340-1.

7. S. Mayor and C. Salazar, "Intrafamily violence. A current health problem," Gac. Medica Spirituana, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 96–105, 2019, [Online]. Available: http://revgmespirituana.sld.cu.

8. World Health Organization, "Violence against Women," WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

9. L. Telles, To. Valença, A. Barros, and A. da Silva, "Domestic violence in the COVID-19 pandemic: a forensic psychiatric perspective," Brazilian J. Psychiatry, vol. 0, no. 1, pp. 5–6, 2020, doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1060.

10. N. Hierrezuelo, P. Fernández, and A. León, "Intrafamilial Violence against Women from a Medical Office in Santiago de Cuba," Rev. Cuba. Med. Gen. Integr. , vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5106-3085.

11. A. Davalos, E. Barrera, A. Emigdio, N. Blanco, and B. Velez, "Family functionality and violence in adolescent women of Acapulco, Mexico," Rev. Dilemmas Contemp. Polit. and values, pp. 1–14, 2021, Accessed: Dec. 09, 2022. [OR nline]. Available: https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/dilemas/v8nspe4/2007-7890-dilemas-8-spe4-00067.pdf.

12. H. Boxall, R. Brown, and A. Morgan, "The prevalence of domestic violence among women during the COVID-19 pandemic," Aust. Inst. Criminol. , pp. 1–19, 2 020, Accessed: Dec. 04, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-07/sb28_prevalence_of_domestic_violence_among_women_during_covid-19_pandemic.pdf.

13. B. Zheng et al. , "The prevalence of domestic violence and its association with family factors: A cross-sectional study among pregnant women in urban communities of Hengyang City, China," BMC Public Health, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–9, May 2020, doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08683-9.

14. P. Sharma and A. Khokhar, "Domestic violence and Coping strategies among married adults during lockdown due to Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in India: A cross-sectional study," Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. , vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1873–1880, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.59.

15. K. Orozco, L. Jimenéz, and L. Cudris, "Mujeres víctimas de violencia intrafamiliar en el norte de Colombia," Rev. Ciencias Soc. vol. XXVI, no. 2, pp. 56–68, 2020, Accessed: Dec. 04, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7500743.

16. P. Leon, W. Ruiz, M. Fiestas, M. Basillo, and J. Morales, "Violencia Física, psico y sexual en mujeres residentes de un distrito de Lima," Peruvian J. Heal. Care Glob. Heal. , vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 44–50, 2021, doi: 10.22258/HGH.2021.52.94.

17. C. Fernández and P. Baptista, "Research Methodology." p. 634, 2015, [Online]. Available: http://observatorio.epacartagena.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/metodologia-de-la-investigacion-sexta-edicion.compressed.pdf.

18. D. Olson, "FACES IV and the Circumplex Model: Validation Study," J. Marital Fam. Ther. , vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 64–68, 2011, [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x.

FINANCING

No financing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Rosa Perez-Siguas, Hernan Matta-Solis, Eduardo Matta-Solis, Luis Perez-Siguas, Victoria Tacas-Yarcuri, Hernan Matta-Perez, Alejandro Cruzata-Martinez, Brian Meneses-Claudio.

Data curation: Rosa Perez-Siguas, Hernan Matta-Solis, Eduardo Matta-Solis, Luis Perez-Siguas, Victoria Tacas-Yarcuri, Hernan Matta-Perez, Alejandro Cruzata-Martinez, Brian Meneses-Claudio.

Formal analysis: Rosa Perez-Siguas, Hernan Matta-Solis, Eduardo Matta-Solis, Luis Perez-Siguas, Victoria Tacas-Yarcuri, Hernan Matta-Perez, Alejandro Cruzata-Martinez, Brian Meneses-Claudio.

Research: Rosa Perez-Siguas, Hernan Matta-Solis, Eduardo Matta-Solis, Luis Perez-Siguas, Victoria Tacas-Yarcuri, Hernan Matta-Perez, Alejandro Cruzata-Martinez, Brian Meneses-Claudio.

Drafting - original draft: Rosa Perez-Siguas, Hernan Matta-Solis, Eduardo Matta-Solis, Luis Perez-Siguas, Victoria Tacas-Yarcuri, Hernan Matta-Perez, Alejandro Cruzata-Martinez, Brian Meneses-Claudio.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Rosa Perez-Siguas, Hernan Matta-Solis, Eduardo Matta-Solis, Luis Perez-Siguas, Victoria Tacas-Yarcuri, Hernan Matta-Perez, Alejandro Cruzata-Martinez, Brian Meneses-Claudio.