doi: 10.56294/saludcyt20241006

ORIGINAL

Scale of Fear of Funa in Social Networks (FFSN): Construction and psychometric properties

Escala de Miedo a la Funa en las Redes Sociales (FFSN): Construcción y propiedades psicométricas

Jonathan Martínez-Líbano1

![]() *, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera2

*, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera2

![]() *

*

1Facultad de Educación y Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago, Chile.

2Facultad de Salud y Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Las Américas, Santiago, Chile.

Cite as: Martínez-Líbano J, Yeomans-Cabrera M-M. Scale of Fear of Funa in Social Networks (FFSN): Construction and psychometric properties. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024; 4:1006. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt20241006

Submitted: 17-01-2024 Revised: 27-03-2024 Accepted: 07-05-2024 Published: 08-05-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

Introduction: A funa is a form of public rebuke, often carried out through digital platforms, in which a person or entity is exposed to behaviors considered inappropriate, unfair, or immoral. This practice may include disclosing personal or professional information about the person or entity, often seeking to generate a social reaction or collective punishment. This research aimed to construct and validate a scale to measure the fear of funa in social networks.

Method: the present study had four phases, with a total sample of n=901:(1) construction, validation, and adjustment of the items by experts (n=10),(2) pilot application n=50, (3) application for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) n=319 and (4) application for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) n=522.

Results: the EFA revealed two underlying factors in the scale, "Anxiety about funas in social networks" and "Fear of the consequences of funas in social networks". The confirmatory factor analysis showed a good psychometric fit of the model. The CFA showed a good psychometric fit: χ² (19) = 78,999, p < 0,001; RMR = 0,051; GFI = 0,961; RMSEA = 0,078; NFI = 0,967; RFI = 0,952; IFI = 0,975; TLI = 0,963; CFI = 0,975; PRATIO = 0,679; PNFI = 0,656; PCFI = 0,662.

Conclusions: this research aimed to construct and validate a scale to measure the fear of funa in social networks. The constructed FFSN is valid and showed a good psychometric fit.

Keywords: Funa; Funas; Social Networks; Mental Health.

RESUMEN

Introducción: una funa es una forma de reprimenda pública, a menudo realizada a través de plataformas digitales, en la que se exponen a una persona o entidad comportamientos considerados inapropiados, injustos o inmorales. Esta práctica puede incluir la divulgación de información personal o profesional sobre la persona o entidad, a menudo buscando generar una reacción social o un castigo colectivo. Esta investigación tuvo como objetivo construir y validar una escala para medir el miedo a la funa en las redes sociales.

Método: el presente estudio tuvo cuatro fases, con una muestra total de n=901: (1) construcción, validación y ajuste de los ítems por expertos (n=10), (2) aplicación piloto n=50, (3) aplicación para análisis factorial exploratorio (AFE) n=319 y (4) aplicación para análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) n=522.

Resultados: el AFE reveló dos factores subyacentes en la escala, "Ansiedad por las funas en las redes sociales" y "Miedo a las consecuencias de las funas en las redes sociales". El análisis factorial confirmatorio mostró un buen ajuste psicométrico del modelo. El AFC mostró un buen ajuste psicométrico: χ² (19) = 78,999, p < 0,001; RMR = 0,051; GFI = 0,961; RMSEA = 0,078; NFI = 0,967; RFI = 0,952; IFI = 0,975; TLI = 0,963; CFI = 0,975; PRATIO = 0,679; PNFI = 0,656; PCFI = 0,662.

Conclusiones: el objetivo de esta investigación fue construir y validar una escala para medir el miedo a la funa en las redes sociales. La FFSN construida es válida y mostró un buen ajuste psicométrico.

Palabras clave: Funa; Funas; Redes Sociales; Salud Mental.

INTRODUCTION

The fear of receiving a "funa" on social networks is a relatively new phenomenon that generates psychological, social, and even labor problems.(1) Today, funa is a method that can be considered a way of taking justice into one's own hands to assert or defend one's rights with social repercussions in the face of harm caused by a third party.(2) In other words, the term funar (verb) is used to refer to the action of publicly exposing a person or entity, generally through social networks or other media, to report their actions, behaviors, or conducts that are considered inappropriate, unjust or morally questionable, thereby seeking to take justice into one's own hands, given the dissatisfaction due to the justice system.(3) The "funa" concept is intertwined with the word "escrache," used by Spanish speakers. According to Bonaldi's definition, escrache is a rebuke to provoke social condemnation through the publication of a human rights violation, breaking anonymity; it can also happen that the facts are not anonymous but are carried out under a sense of normality.(4) On the other hand, Manso points out that escrache is a rebuke that must be public and used fundamentally for an accusation of a singular person.(5) Funa and escrache are practically the same facts (public denunciation in search of social condemnation). However, escrache is only directed at individuals, and funa can be directed at persons or entities. In this sense, when a rebuke of this type is made to an individual, funa and escrache are synonymous and appropriate words. Still, if an entity is denounced, escrache is not a word that can define the action.

Evolution of the concept of "Funa"

"Funa" is a word used in Chile; it has its origin in Mapudungun (the language of the Mapuche native people), coming from the concept "funan," which means to rot, something that is left in a place, despised and abandoned by everyone, and that suffers deterioration or something else negative.(6) The origin of the concept, or rather of its use as we know it today, dates to the end of the 20th century, after the arrest of Augusto Pinochet in London in October 1998. Human rights demonstrators began to gather in vigils organized by the Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos;(7) likewise, after the arrest of Augusto Pinochet, the organization "Comisión Funa en Chile" was initiated, which has no political militancy, and was joined by various youth, political and student organizations.(8) These organizations acted under the purpose of "funar" the people who committed or were accomplices of human rights violations during the military dictatorial regime established in Chile between September 11, 1973, and March 11, 1990.(2) To achieve their objective, the members of the commission and the associations in question went to the private homes or workplaces of the accused in a massive and boisterous demonstration.(9) From here, popular justice is sought, and "transforming memory into action" is a novel way of "denouncing impunity".(10)

The term "funa" is colloquially used in the language of Chilean society as a public act of reproach through which an unjust act is attributed to a person.(11) With it, justice that formal institutions do not provide is pursued(12) and constitutes an exercise of social chastisement, public and collective debate that is explicitly differentiated from other acts of personal revenge,(6) being a kind of public denunciation, in which a person makes known a reprehensible situation to expose the culprit and alert their environment.(13)

Currently, the funa can be considered as an informal complaint since it is not carried out through institutional channels (courts and tribunals) and is generally carried out through social networks, such as X (Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, among others, in which the aim is to discredit a person for having committed a fault and thus affect his reputation before others.(11) It is a method of public denunciation in which it is made explicit what has happened to someone with a company, a place, a person, or a particular event through a story that can be accompanied by images, videos, conversations, or other audiovisual element that corroborates what has been exposed,(14) denaturalizing the field of privacy and opening it.(7)

Funas can be confused with other phenomena

As reviewed in the definitions presented, funa focuses on the public denunciation of a person or entity for acts deemed immoral or illegal and is driven by social justice motives. In contrast, cyberbullying or virtual lynching, terms that are considered synonymous, are the sustained, online harassment of a person, which often includes threats, intimidation, and bullying(15) but has no specific social justice purpose and can be purely malicious.(16) Trolling is another phenomenon that can be confused with funa. However, trolling aims to annoy, provoke, or mislead someone online, often for fun;(17) it does not usually focus on serious accusations or attempts at social justice.(18) Therefore, we can identify funa when it seeks to expose and publicly condemn specific behavior, often based on serious accusations.(6)

Risks Associated with Funas

The funa through social networks is typical of today's youth(19) and may be one of the new psychological problems derived from the use and abuse of social networks.(20) Young people are not indifferent to what happens in their environment. They believe they have something to say and want to create a fairer world.(21) From this point, it must be understood that the search for justice through public "funas," although legitimate in their substance, carries consequences that can be dangerous or disappointing for those who seek the vindication of an unjust and traumatic experience.(22) In this line, criminal lawyer Carlos Silva indicates that, if the accusation is true, there is no problem for the one who "funas"; however, if the accused through the networks decides to resort to justice and turns out to be innocent of what he is accused of, the victim would become a victimizer, risking high penalties.(23) On many occasions, the good name and honor of people end up being exposed daily in social networks because, in many cases, there is no control or filter to make any kind of comment or publication in these media.(24) From this point of view, if a person is falsely accused, they will have little credibility in the social context; in social networks, the information will be shared, trying to contribute to the supposed justice without verifying the veracity of the complaint.(25) The person alluded to or falsely accused could defend themself in court.(26) However, the person's reputation could have been unfairly damaged. Unfortunately, it is common for perspectives on unwitnessed events to be widely disseminated on social networks, with no consequences for many who have spread falsehoods.(27)

It is necessary to make it known that funas through social networks can have a profound and lasting impact on a person's life, affecting their emotional well-being and mental health,(1) reputation, social life, and professional prospects.(11) Reputational damage is one of the most immediate and notable consequences of a "funa," as public perception can change drastically, and the person may lose the trust of friends, family, and colleagues.(7) Along with the damage to reputation, there are adverse effects in other areas of the person's life, such as the loss of a job and job opportunities, meaning an impact on the quality of life of the person and their family, giving a drastic turn in their personal, social, and economic situation.(28) The above has generated fear in many people who could be exposed to the scrutiny of social networks with or without background to be realized.(8)

Based on the background, this research aimed to construct and validate a scale that measures the fear of being a target of funa in social networks. To meet the above objective, four specific objectives were defined: 1) To construct and validate the items and/or reagents of the scale through expert judges; 2) To apply the instrument in a pilot test; 3) To perform an exploratory factor analysis; 4) To perform a confirmatory factor analysis of the scale.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Design

The present FFSN development and validation study had a mixed research design (Hernández Sampieri, 2018), given that it included exploratory and cross-sectional components.

Procedure

The present study consisted of four phases. The first phase consisted of the scale design, where the items were designed by the researchers and tested by ten expert judges in the social sciences. Concordance was analyzed and determined using the Aiken coefficient. Based on the indications provided by the experts, the wording was adjusted, and the items that did not apply or did not better describe the phenomenon to be measured were eliminated. The items that presented a high level of agreement (< 0,80) among the expert judges were maintained. In the second stage, a pilot test was applied with 50 people; they were asked to explain whether the items were easy to understand. From this pilot test, final adjustments were made to the wording. In the third stage, a sample of 319 people was taken, and an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to determine the structure of the scale. In the fourth stage, the instrument was applied to a sample of 522 people, and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. Likewise, the DASS-21 was applied to evaluate convergent validity in this last stage.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Variables: To learn more about the characteristics of the sample, a questionnaire asking for age, gender, and marital status, among other things, was carried out.

DASS-21 (Depression Anxiety Stress Scales - 21 Items): This psychological questionnaire was designed to measure levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. Lovibond and Lovibond developed it in 1995 (30). The DASS-21 is a shorter version of the original DASS, which contained 42 items. This instrument has been widely used in various clinical and research contexts and presents good reliability indicators for the Chilean population(31) Composed of 21 items divided into three scales, each with seven questions, the questionnaire is based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always). Participants are asked to indicate their feelings concerning each statement during the past week. For example, one item might be "I felt sad and depressed," and response options range from "It did not apply to me at all" to "It applied to me a lot or most of the time." Scores on each scale are summed individually to assess levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, making it a valuable tool within a broader psychological assessment.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Among the criteria for inclusion of the expert judges (Phase 1), all had to be professionals in social sciences, have a master's degree, and be knowledgeable and related to the funa phenomenon. Incomplete questionnaires were not included.

The inclusion criteria for the sample to which the instrument was applied in the three instances (Stages 2, 3, and 4) were that they were 18 or older, were social network users, and had a residence in Chile. Incomplete questionnaires were not included.

Statistical Analysis

The data analysis of this study was conducted in several phases, using a mixed approach to assess the validity and reliability of the Fear of Funas in Social Networks Scale (FFSN). The initial development and validation of the FFSN scale items were conducted in the first phase. Ten expert judges, including psychologists, social workers, and lawyers, designed and evaluated twenty items. These experts analyzed the items regarding quality and relevance using the Aiken coefficient. Items with a concordance below 0,80 were eliminated, resulting in a reduced scale version with ten items. In the second phase, the reduced scale was applied to a sample of 319 people using snowball sampling. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to examine the underlying structure of the scale. The Maximum Likelihood method was used for factor extraction, and a Varimax rotation was applied to facilitate interpretation. The EFA revealed two main factors: "Anxiety before funas in social networks" and "Fear of the consequences of funas in social networks". The scale's reliability was assessed by Cronbach's alpha and omega, indicating high internal consistency. The third phase involved applying the scale to a second sample of 522 people to perform a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using SPSS AMOS. The CFA confirmed the bifactor structure of the scale and showed good psychometric fit on several measures, including the chi-square index, RMR, GFI, RMSEA, and several incremental fit indices such as NFI, RFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI. The following criteria were used to determine the goodness of fit: (1) CFI≥0,9; (2) TLI≥0,95; (3) RMSEA<0,08; (4) SRMR<0,08; (5) goodness of fit p>0,05 (32,33). In addition, the convergent validity of the FFSN scale was assessed by correlating it with the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress subscales of the DASS-21. Statistically significant correlations were found, suggesting a positive relationship between fear of funas in social networks and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. This multifaceted approach to data analysis ensured a comprehensive assessment of the validity and reliability of the FFSN scale, providing a robust tool for measuring fear of funas on social networks.

Ethical criteria

The present research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education and Social Sciences of the Universidad Andrés Bello under registration number 024/2023.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Design of the Scale of Fear of Funas in Social Networks

The first part consisted of expert judges elaborating and validating the scale items. Twenty items were designed to capture the essence of the construct of fear of funas through social networks. These items were presented to the ten experts, six psychologists, two social workers, and two lawyers. The mean age of the experts was 44 years (SD = 4,90), and they had a mean of 16,8 years of professional experience (SD = 5,00), all with a master's degree. These experts analyzed the items in terms of quality and relevance. Based on the Aiken V analysis, it was decided to eliminate all items below 0,80 concordance, leaving ten items for the second phase.

|

Table 1. Aiken V-analysis of the expert judges' evaluation of the Scale of the Fear of Funas in Social Networks |

|||||||||

|

# |

Item |

Pertinence |

Clarity |

||||||

|

Prom |

V Aiken |

IC95 % |

Prom |

V Aiken |

IC95 % |

||||

|

1 |

I am distressed at the thought of someone posting something about me on social media. |

20,2 |

0,73 |

0,55 |

0,85 |

20,8 |

0,93 |

0,78 |

0,98 |

|

2 |

It would be terrible if someone posted something about me on social media. |

20,4 |

0,80 |

0,62 |

0,90 |

20,5 |

0,83 |

0,66 |

0,92 |

|

3 |

It would be hard to get over someone posting something negative about me on social media. |

20,0 |

0,66 |

0,48 |

0,80 |

20,5 |

0,83 |

0,66 |

0,92 |

|

4 |

When I see a funa on social media, I think about what I would do if it were me. |

20,4 |

0,80 |

0,62 |

0,90 |

20,8 |

0,93 |

0,78 |

0,98 |

|

5 |

I get anxious when I think about someone posting something that affects my honor or image on social media. |

20,9 |

0,96 |

0,83 |

0,99 |

20,8 |

0,93 |

0,78 |

0,98 |

|

6 |

When I think someone could make me a target of a funa, I get a stomach ache. |

20,5 |

0,83 |

0,66 |

0,92 |

20,9 |

0,96 |

0,83 |

0,99 |

|

7 |

I have been afraid that someone will make me a target of a funa on social networks. |

20,7 |

0,90 |

0,74 |

0,96 |

30,0 |

10,0 |

0,88 |

10,0 |

|

8 |

Funas make me anguish |

20,3 |

0,76 |

0,59 |

0,88 |

20,9 |

0,96 |

0,83 |

0,99 |

|

9 |

The mere thought that someone might make me a target of a funa makes me anxious. |

20,5 |

0,83 |

0,66 |

0,92 |

20,9 |

0,96 |

0,83 |

0,99 |

|

10 |

I've had dreams where I see myself being a target of a funa |

20,0 |

0,66 |

0,48 |

0,80 |

20,9 |

0,96 |

0,83 |

0,99 |

|

11 |

Sometimes, I avoid conflicts just because of the fear of being the target of a funas |

20,5 |

0,83 |

0,66 |

0,92 |

30,0 |

10,0 |

0,88 |

10,0 |

|

12 |

I believe that anyone could be the target of a funas |

10,9 |

0,63 |

0,45 |

0,78 |

20,9 |

0,96 |

0,83 |

0,99 |

|

13 |

I've been threatened with making me the target of a funa |

20,3 |

0,76 |

0,59 |

0,88 |

20,7 |

0,90 |

0,74 |

0,96 |

|

14 |

When someone takes a picture of me or videotapes me, I think that they could use these images to make me a target of a funa. |

20,2 |

0,73 |

0,55 |

0,85 |

20,8 |

0,93 |

0,78 |

0,98 |

|

15 |

If I were made a target of a funa, it would profoundly affect my life. |

20,7 |

0,90 |

0,74 |

0,96 |

20,9 |

0,96 |

0,83 |

0,99 |

|

16 |

Someone threatened to make me a target of a funa |

20,0 |

0,66 |

0,48 |

0,80 |

20,7 |

0,90 |

0,74 |

0,96 |

|

17 |

If I were to be made the target of a funa, it would be tough to cope with it |

20,6 |

0,86 |

0,70 |

0,94 |

30,0 |

10,0 |

0,88 |

10,0 |

|

18 |

I think that if I were a target of a funa, I would lose my loved ones. |

20,6 |

0,86 |

0,70 |

0,94 |

20,8 |

0,93 |

0,78 |

0,98 |

|

19 |

I feel that I have a reason to be a target of a funa in social networks |

20,2 |

0,73 |

0,55 |

0,85 |

20,8 |

0,93 |

0,78 |

0,98 |

|

20 |

I feel that a funa could be used to take revenge on me. |

20,3 |

0,76 |

0,59 |

0,88 |

20,8 |

0,93 |

0,78 |

0,98 |

Phase 2: Pilot Test

In the second phase, 50 people answered the FFSN regarding comprehension of the questions. A few adjustments were made to the verb election, organization within sentences, and organization within ideas.

Phase 3: Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Scale Fear of Funas in Social Networks

In the third phase of the present study, through a snowball methodology, a sample of 319 persons was collected: 62,1 % (198) women and 37,9 % (121) men with a mean age of 27,81 years (SD = 9,53), all of them of legal age ( ≥18y), all of Chilean nationality. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the scale.

|

Table 2. Descriptive statistics |

|||||||||||||||

|

Items |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Skew |

Kurt |

F2 |

F4 |

F5 |

F6 |

F7 |

F9 |

F11 |

F15 |

F17 |

F18 |

|

F2 |

3,3417 |

4,0000 |

1,27846 |

-0,343 |

-0,977 |

- |

|||||||||

|

F4 |

2,7680 |

3,0000 |

1,30412 |

0,103 |

-1,188 |

0,444** |

- |

||||||||

|

F5 |

3,0940 |

3,0000 |

1,32368 |

-0,174 |

-1,147 |

0,603** |

0,517** |

- |

|||||||

|

F6 |

2,3887 |

2,0000 |

1,23344 |

0,541 |

-0,676 |

0,436** |

0,516** |

0,648** |

- |

||||||

|

F7 |

2,0878 |

2,0000 |

1,26086 |

0,923 |

-0,316 |

0,315** |

0,491** |

0,428** |

0,595** |

- |

|||||

|

F9 |

2,3762 |

2,0000 |

1,22969 |

0,446 |

-0,954 |

0,454** |

0,510** |

0,639** |

0,731** |

0,682** |

- |

||||

|

F11 |

2,0846 |

2,0000 |

1,21923 |

0,927 |

-0,193 |

0,215** |

0,355** |

0,375** |

0,417** |

0,586** |

0,528** |

- |

|||

|

F15 |

2,8370 |

3,0000 |

1,31456 |

0,095 |

-1,150 |

0,464** |

0,394** |

0,567** |

0,443** |

0,307** |

0,515** |

0,325** |

- |

||

|

F17 |

2,8276 |

3,0000 |

1,26580 |

0,075 |

-1,060 |

0,482** |

0,372** |

0,577** |

0,488** |

0,319** |

0,533** |

0,331** |

0,801** |

- |

|

|

F18 |

2,2382 |

2,0000 |

1,29086 |

0,775 |

-0,512 |

0,181** |

0,218** |

0,325** |

0,303** |

0,244** |

0,298** |

0,283** |

0,507** |

0,526** |

- |

The reliability analysis of the scale showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0,891 and an omega of 0,893, indicating a high level of internal consistency. These values suggest that the scale items are consistent in their measurement and that the scale is reliable. Table 3 shows that eliminating any item would not significantly modify the scale's reliability indices.

|

Table 3. Table of Item Analysis and Scale Reliability |

||||

|

Item |

Scale Mean if Item Deleted |

Scale Variance if Item Deleted |

Corrected Item-Total Correlation |

Cronbach's Alpha if Item Deleted |

|

F2 |

22,7022 |

68,449 |

0,554 |

0,886 |

|

F4 |

23,2759 |

67,496 |

0,589 |

0,883 |

|

F5 |

22,9498 |

64,375 |

0,738 |

0,873 |

|

F6 |

23,6552 |

65,893 |

0,719 |

0,874 |

|

F7 |

23,9561 |

67,564 |

0,611 |

0,882 |

|

F9 |

23,6677 |

64,971 |

0,773 |

0,871 |

|

F11 |

23,9592 |

69,718 |

0,521 |

0,888 |

|

F15 |

23,2069 |

65,655 |

0,677 |

0,877 |

|

F17 |

23,2163 |

65,881 |

0,697 |

0,876 |

|

F18 |

23,8056 |

70,667 |

0,437 |

0,894 |

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0,881, indicating very good adequacy for factor analysis since values above 0,80 are considered desirable. This suggests that the proportion of variance between variables that could be common is sufficiently high for factor analysis. Bartlett's test of sphericity resulted in an approximate chi-square value of 1742,208 with 45 degrees of freedom and was significant (p < 0,001). This indicates that the variables are sufficiently correlated and not independent, a prerequisite for performing a factor analysis. The significance of Bartlett's test suggests that the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix and that it is appropriate to proceed to factor analysis.

|

Table 4. Total Explained Variance |

|||||||||

|

Factor |

Initial Eigen values |

Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings |

Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings |

||||||

|

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

|

|

1 |

5,138 |

51,383 |

51,383 |

4,702 |

47,018 |

47,018 |

3,112 |

31,120 |

31,120 |

|

2 |

1,270 |

12,702 |

64,085 |

0,962 |

9,622 |

56,640 |

2,552 |

25,520 |

56,640 |

|

3 |

0,966 |

9,660 |

73,744 |

||||||

|

4 |

0,561 |

5,611 |

79,355 |

||||||

|

5 |

0,539 |

5,392 |

84,746 |

||||||

|

6 |

0,455 |

4,547 |

89,293 |

||||||

|

7 |

0,384 |

3,843 |

93,136 |

||||||

|

8 |

0,267 |

2,674 |

95,810 |

||||||

|

9 |

0,227 |

2,272 |

98,083 |

||||||

|

10 |

0,192 |

1,917 |

100,000 |

||||||

|

Extraction Method: Maximum Likelihood |

|||||||||

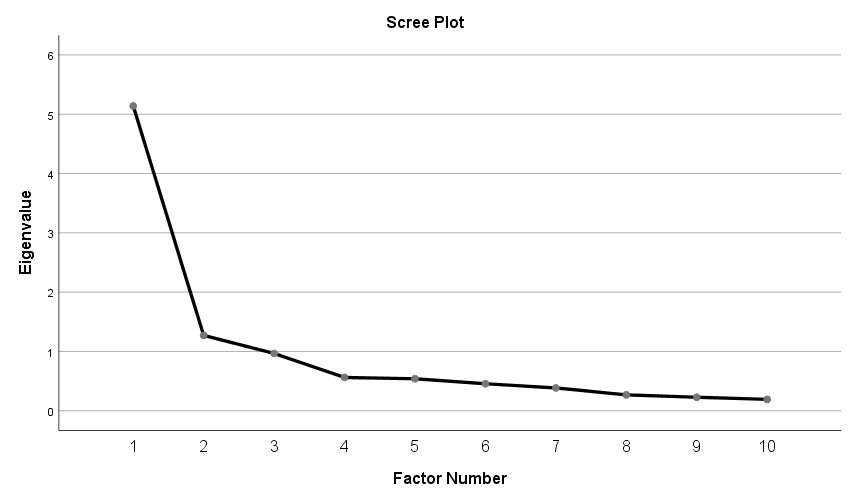

The following results were observed in the factor analysis performed by the Maximum Likelihood method. The initial eigenvalues indicated that the first factor had an eigenvalue of 5,138, explaining 51,383 % of the total variance. The second factor had an eigenvalue of 1,270, contributing an additional 12,702 % to the variance explained, resulting in a cumulative percentage of variance explained of 64,085 %. The eigenvalues of the subsequent factors were lower: the third factor explained an additional 9,660 % of the variance, and so on up to the tenth factor.

After extraction, the adjusted eigenvalues showed that the first factor explained 47,018 % of the variance. In comparison, the second factor explained an additional 9,622 %, adding to a cumulative total of 56,640 % of the variance. The rotation of the factors redistributed the explained variance, with the first factor now explaining 31,120 % and the second factor 25,520 %, keeping the cumulative total at 56,640 %.

Figure 1. Screenshot diagram of the Scale Fear of Funa in Social Networks

As shown in figure 1, the results suggest that the first two factors are the most significant in explaining the variance of the data, which highlights their relevance in the factor structure of the set of items analyzed.

|

Table 5. Matrix of rotated factors |

|||

|

Ítems |

Factor |

Factor Name |

|

|

1 |

2 |

||

|

F9 The thought of someone making me the target of a funa makes me anxious. |

0,808 |

0,355 |

Anxiety Facing Funas in Social Networks (AFFSN)

|

|

F7 I have been afraid that someone will make me a target of a funa on social networks. |

0,78 |

0,116 |

|

|

F6 When I think that someone might defame me, I feel sick to my stomach. |

0,746 |

0,324 |

|

|

F5 When I think about someone posting something that affects my honor or image on social networks, I get anxious. |

0,575 |

0,504 |

|

|

F11 Sometimes I avoid conflicts just because I am afraid of being the target of a funa |

0,569 |

0,193 |

|

|

F4 When I see a funa on social networks, I think about what I would do if it were me |

0,561 |

0,279 |

|

|

F17 If I were to be the target of a funa, it would be tough to cope with it |

0,275 |

0,862 |

Fear of the Consequences of Funas in Social Networks (FCFSN) |

|

F15 I think that if I were to be the target of a funa, it would deeply affect my life |

0,258 |

0,846 |

|

|

F18 I think that if I were to be the target of a funa, I would lose my loved ones |

0,165 |

0,536 |

|

|

F2 It would be terrible if someone published something about me on social networks. |

0,396 |

0,439 |

|

|

Extraction method: maximum likelihood |

|

|

|

The rotated factor matrix (Table 5) reveals the loading of each item on the two factors identified after Varimax rotation. These factors were labeled "Anxiety about funas in social networks" and "Fear of the consequences of funas in social networks". Items F9, F7, F6, F5, F11 and F4 show higher loadings on Factor 1, while items F17, F15 and F18 have higher loadings on Factor 2. Item F2 shows moderate loadings on both factors. Based on the above, the researchers decided to eliminate item 2 for the application process to the final sample. Factor loadings indicate the correlation of each item with the corresponding factor, suggesting that items grouped in each factor share a common variance that may represent a specific underlying construct. Varimax rotation, an orthogonal rotation technique, was used to maximize the variance of the squares of the loadings on each factor, thus facilitating factor interpretation.

Phase 4: Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Scale of Fear of Funas in Social Networks

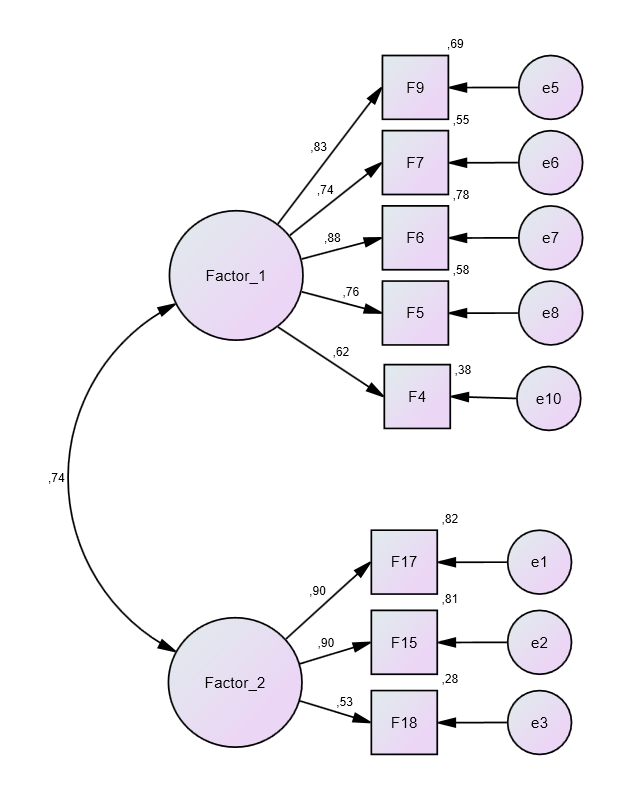

For the final phase of scale construction, a new sample of 522 people was taken, 64 % (334) women and 36 % (188) men, with a mean age of 32,75 years (SD = 10,305). The result of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using SPSS AMOS to assess the factor structure of the FFSN scale. The chi-square index was significant, χ² (19) = 78,999, p < 0,001, with a chi-square ratio in degrees of freedom of 4,158, suggesting a moderate model fit. The RMR was 0,051, and the GFI was 0,961, indicating a good model fit; the RMSEA was 0,078 (90 % CI 0,061 to 0,096), which is at the upper limit of the acceptable range; the incremental fit indices were robust, with an NFI of 0,967, an RFI of 0,952, an IFI of 0,975, a TLI of 0,963 and a CFI of 0,975. The PRATIO was 0,679, the PNFI was 0,656, and the PCFI was 0,662, indicating a reasonable fit of the model considering its parsimony. These results suggest that the model fits several key measures well, although the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom is somewhat high. The incremental fit indices and parsimony-adjusted measures support the model's adequacy. The RMSEA indicates a reasonable fit, although it is at the upper limit of the desirable range.

|

Table 6. Análisis de factores |

|||||||

|

CMIN/DF |

GFI |

IFI |

AGFI |

NFI |

TLI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

|

4,158 |

0,961 |

0,975 |

0,926 |

0,967 |

0,963 |

0,975 |

0,078 |

Figure 2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Scale of Fear of Funas in Social Networks

Convergence Validation

Convergent validation of the FFSN was carried out by evaluating its correlations with the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress subscales of the DASS-21. The results indicated statistically significant correlations in all cases, suggesting a satisfactory convergent validity of the scale. The results indicated statistically significant correlations in all cases, suggesting satisfactory convergent validity of the scale.

In particular, the correlation between the FFSN total score and the Depression subscale of the DASS-21 was 0,217, indicating a positive and moderate relationship. This correlation suggests that an increased fear of funas in social networks is associated with increased depressive symptoms. Similarly, positive and significant correlations were found with the Anxiety subscale (0,252) and the Stress subscale (0,268), reinforcing the association between fear of funas and an increase in anxiety and stress-related symptoms.

When the scale was broken down into its two constituent factors, similar correlation patterns were observed, although with some variations in magnitude. "Factor 1: Anxiety before funas in social networks" showed correlations of 0,185 with Depression, 0,218 with Anxiety, and .227 with Stress. On the other hand, "Factor 2: Fear of the consequences of funas in social networks" presented slightly higher correlations, being 0,230 with Depression, 0,258 with Anxiety, and 0,284 with Stress.

These findings support the convergent validity of the FFSN Scale, demonstrating that this scale is significantly related to relevant psychological constructs measured by the DASS-21. The consistency in positive and significant correlations reinforces the credibility of the scale as a valid instrument for assessing fear and anxiety associated with funas in social networks.

|

Table 7. Correlations between the Scale of Fear of Funas in Social Networks and the DASS-21 |

|||

|

|

Depression |

Anxiety |

Stress |

|

Total Fear of Funas on Social Networks Scale |

0,217** |

0,252** |

0,268** |

|

Factor 1: Anxiety Facing the Funa in Social Networks". |

0,185** |

0,218** |

0,227** |

|

Factor 2: Fear of the Consequences of Funas in Social Networks". |

0,230** |

0,258** |

0,284** |

|

**.Correlation is significant at the 0,01 level (2-tailed) |

|||

DISCUSSION

The explosion of social networks and the difficulties of justice in processing criminal cases have been breeding grounds for people to use new methods to seek justice by their means, which translates into funas through social networks. The fear of being funked in social networks is a new phenomenon that is becoming evident by the concern that people denote. Some people avoid many situations to avoid falling into this practice.

The objective of the present study was to construct and validate a scale that measures fear of funa through social networks, which was carried out through phases: the design and adjustment of the items, initial sampling for the exploratory factor analysis, then a final sampling with which the confirmatory factor analysis was performed and validation by convergence with the DASS-21. The psychometric indicators were good. The scale's reliability showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0,891 and an omega of 0,893, indicating a high level of internal consistency. These values suggest that the scale items are consistent in their measurement and that the scale is reliable. The chi-square index was significant, χ² (19) = 78,999, p < 0,001, with a chi-square ratio in degrees of freedom of 4,158, suggesting a moderate model fit. The RMR was 0,051, and the GFI was 0,961, indicating a good model fit. The RMSEA was 0,078 (90 % CI [0,061, 0,096]), which is at the upper limit of the acceptable range, the incremental fit indices were robust, with an NFI of 0,967, an RFI of 0,952, an IFI of 0,975, a TLI of 0,963, and a CFI of 0,975. The PRATIO was 0,967, an RFI of 0,952, an IFI of 0,975, a TLI of 0,963, and a CFI of 0,975. The PRATIO was 0,679, the PNFI was 0,656, and the PCFI was 0,662, indicating a reasonable fit of the model considering its parsimony. These results suggest that the model fits several key measures well, although the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom is somewhat high. The incremental fit indices and parsimony-adjusted measures support the model's adequacy. The RMSEA indicates a reasonable fit, although it is at the upper limit of the desirable range.

The FFSN scale assesses two factors: Anxiety about funas in social networks and fear of the consequences of funas in social networks.

Anxiety before the funa on social networks refers to the immediate and worrying emotional response that a person experiences before the possibility of being funa on social networks. Anxiety in this context implies a state of uneasiness, nervousness, or fear at the possibility of being singled out or publicly shamed on digital platforms. This factor could include symptoms such as constant worry, tension, and a sense of imminent threat related to social media interaction. People with elevated funa anxiety may be more vigilant or worried about their online posts and interactions, fearing that they may trigger an adverse reaction or public scrutiny.

Fear of the consequences of funas on social networks focuses on the fear of the long-term repercussions that may arise due to being the target of funas. This includes concern about reputational damage, professional or academic consequences, and the impact on personal relationships. In this case, fear is not limited to the immediate experience of being subjected to funas but also encompasses concern about possible sequelae that may persist long after the initial event. People who score high on this factor may experience fear of losing job opportunities, social ostracism, or facing continued hostility and judgment in their virtual and natural environments.

The convergent validation of the Social Network Fear of Funas Scale was carried out by evaluating its correlations with the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress subscales of the DASS-21. The results indicated statistically significant correlations in all cases, suggesting satisfactory convergent validity of the scale.

In each one of the steps, the soundness of the instrument was verified, which will allow us to initiate the study of the funa phenomenon more scientifically and to be able to determine possible risk factors and psychological consequences of this phenomenon.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of the present study is that although the sample is above what is recommended by various authors in the field of psychometrics, it is limited to a Chilean population, so it cannot reflect the experiences of these people in other cultural or geographical contexts. Another element that can be qualified as a limitation is the use of a cross-sectional design, which prevents establishing generalizations to the entire Chilean population, much less establishing causal relationships of the phenomenon. Also, the scale is based on a self-report measure, which may be subject to biases such as social desirability or lack of awareness in the responses, which could affect the answers' accuracy.

Study Projections

Among the projections of this study is the opportunity to have a psychometric scale to measure this phenomenon in different realities. We should not fail to understand that this is a Latin American phenomenon, so it can begin to be measured in other countries of our continent to validate and establish the prevalence of the phenomenon by country. In addition, it is essential to understand that longitudinal studies can be conducted to see how the phenomenon of funas can affect people who present this fear or who have been funas throughout their lives. The scale can be integrated into broader studies on cyberbullying, online reputation, and mental health in the digital age, providing a valuable tool to measure a specific aspect of social network interaction. The findings may contribute to developing psychological theories related to public exposure, fear, and anxiety in digital environments.

CONCLUSION

This research aimed to construct and validate a scale for measuring the fear of being a target of funa on social media (FFSN), an instrument designed to measure the fear and anxiety that people may experience at the possibility of being targeted by funas on digital platforms. The results of the factor analyses revealed a consistent bifactorial structure, distinguishing two main factors: the anxiety about the possibility of being a target of funa and the fear of the long-term consequences of funas. The scale showed good psychometric adjustment, demonstrating robust reliability and validity indices, making the FFSN a valid tool for accurately assessing how the fear of funas on social networks could affect the quality of life and well-being of individuals who are victims of this phenomenon. Finally, this instrument provides a scientific avenue to study the phenomenon of funas on social networks, potentially leading to a significant advancement in the study of digital interactions and their impact on mental health.

REFERENCES

1. Martínez-Líbano J, Bobadilla Olivares V. Motivaciones y Consecuencias Psicológicas de las Funas en Chile : Una Revisión Bibliográfica Motivations and Psychological Consequences of the Funas in Chile : A Bibliographic Review. Ciencia Latina Revista Multidisciplinar. 2021;5(2):2270–83.

2. Jiménez Fredes C, Sepúlveda Cayuqueo C. La funa y sus consecuencias juridicas: una perspectiva del derecho penal [Internet]. [Valparaíso]: Universidad de Valparaíso; 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: https://repositoriobibliotecas.uv.cl/bitstream/handle/uvscl/9365/TesinaJimenez%20y%20Sepulveda.pdf?sequence=1

3. Martínez-Líbano J, Bobadilla V. Motivaciones y Consecuencias Psicológicas de las Funas en Chile: Una Revisión Bibliográfica. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar. 2021 May;5(2):2270–83.

4. Bonaldi P. “Si no hay justicia, hay escrache”. El repudio moral como forma de protesta. Apuntes de Investigación del CECYP [Internet]. 2006 Sep [cited 2024 Apr 16];10(11):9–30. Available from: http://bibliots.trabajosocial.unlp.edu.ar/meran/opac-detail.pl?id1=4638&id2=5819

5. Manso ND. Escraches en Redes Sociales. Aproximaciones Históricas, Medios y Agendas Feministas. Intersecciones en Comunicación [Internet]. 2021 Jul 12 [cited 2024 Apr 16];1(15). Available from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9170196

6. Wood Puga A. “La Funa es más que la Funa en sí” Experiencias de jóvenes que realizaron una funa en contexto de violencia machista. Universidad de Chile. 2021.

7. Schmeisser C. La Funa Aspectos Históricos , Jurídicos Y Sociales. Universidad de Chile; 2019.

8. Vera Gajardo S. La funa feminista. Debates activistas frente a las acusaciones públicas de violencias de género. Anuari del Conflicte Social. 2022;(13).

9. Guthrey HL. “Vigilante” Expressions of Social Memory in Chile: Exploring La Comisión Funa as a Response to Justice Deficits. In: Opuscula historica Upsaliensia [Internet]. Uppsala universitet; 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1518157/FULLTEXT01.pdf

10. Valenzuela Prado L. Escenas, protesta y comunidad. Cine y narrativa en Chile y Argentina (2001-2015). Universum (Talca). 2018;33(2):215–33.

11. Parada Godoy V, Fuentes Suárez G. Autotutela: funas por delitos sexuales y su conveniencia (o no) en un estado de derecho [Internet] [Tesis]. [Santiago]: Universidad de Chile; 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/186511/Autotutela-funas-por-delitos-sexuales-y-su-conveniencia-o-no-en-un-estado-de-derecho.pdf?sequence=1

12. Dudai R. Transitional justice as social control: political transitions, human rights norms and the reclassification of the past. Br J Sociol. 2018;69(3):691–711.

13. Spencer J. Funas en redes sociales un arma de doble filo. Radio UC [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Sep 18]; Available from: https://radiouc.cl/funas-en-redes-sociales-un-arma-de-doble-filo/

14. Duarte Labbé J. Las funas de facebook como evidencia clara del panóptico de foucault en la actualidad 1. Contextos: Estudios De Humanidades Y Ciencias Sociales. 2020;44.

15. Slaughter A, Newman E. New frontiers: Moving beyond cyberbullying to define online harassment. Journal of Online Trust and Safety. 2022;1(2).

16. Bilić V. The role of perceived social injustice and care received from the environment in predicting cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Medijska istraživanja: znanstveno-stručni časopis za novinarstvo i medije. 2014;20(1):101–25.

17. Owen T, Noble W, Speed FC, Owen T, Noble W, Speed FC. Trolling, the ugly face of the social network. New perspectives on cybercrime. 2017;113–39.

18. Coles BA, West M. Trolling the trolls: Online forum users constructions of the nature and properties of trolling. Comput Human Behav. 2016;60:233–44.

19. Calderón C, Restaino M, Rojas C, Sobarzo A. El rol de las redes sociales en la génesis del ‘estallido social.’ Revista de Ciencias Sociales ISSN: 0718-3631. 2021;30(47):66–106.

20. Martínez-Líbano J, González Campusano N, Pereira Castillo J. Las Redes Sociales y su Influencia en la Salud Mental de los Estudiantes Universitarios: Una Revisión Sistemática. REIDOCREA. 2022;11(4):44–57.

21. Grajales CVE, González DEC. Juventud, ciudadanía y posicionamientos políticos: una lectura desde el aula de clase. Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos. 2017;13(1):153–78.

22. Carrasco C. MisAbogados. 2019. p. https://www.misabogados.com/blog/es/el-marco-legal El marco legal de las “funas” en redes sociales. Available from: https://www.misabogados.com/blog/es/el-marco-legal-de-las-funas-en-redes-sociales

23. Pizarro JC. Funas en redes sociales, un arma de doble filo.pdf. Funas en redes sociales, un arma de doble filo [Internet]. 2020 Jan; Available from: http://www.diarioeldia.cl/tendencias/funas-en-redes-sociales-arma-doble-filo

24. Alcántara Farfán JC. Libertad de expresión y las redes sociales en la comisión del delito de difamación, distrito judicial de Ica-2021 [Internet]. Universidad César Vallejo. [Lima]: Universidad César Vallejo; 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/96595

26. Sariego JL. ¿Como se siente un hombre difamado y acusado falsamente?: Verdades como puños. 2018.

27. Yeomans-Cabrera MM. Desinformación. La Segunda [Internet]. 2024 Feb 15 [cited 2024 Apr 9];10–10. Available from: https://www.litoralpress.cl/sitio/Prensa_PaginaCompleta.cshtml?LPKey=WE5VZBEC5JQTKGSRX7ZRM6REYPPTZ5VHWHSBFCRC4OERKFWIDIIRDHFISDEEEUQZRRE5XS2T6DCWA

28. Silva Silva JF. Linchamientos digitales: castigo extrajudicial en entornos digitales. [Santiago]: Universidad Alberto Hurtado; 2022.

29. Hernández Sampieri R. Metodología de la investigación: las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. McGraw Hill México; 2018.

30. Lovibond P, Lovibond S. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Scales (DASS) [Internet]. Vol. 33, Behaviour research and therapy. 1995 [cited 2022 Aug 7]. p. 335–43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

31. Martínez-Líbano J, Torres-Vallejos J, Oyanedel JC, González-Campusano N, Calderón-Herrera G, Yeomans-Cabrera MM. Prevalence and variables associated with depression, anxiety, and stress among Chilean higher education students, post-pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14.

32. Cangur S, Ercan I. Comparison of model fit indices used in structural equation modeling under multivariate normality. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. 2015;14(1):14.

33. Zhang X, Savalei V. Bootstrapping confidence intervals for fit indexes in structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Modeling. 2016;23(3):392–408.

FINANCING

This research was supported by ADIPA, Academia Digital de Psicología y Aprendizaje.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there does not exist an interest conflict.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

Formal analysis: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

Research: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

Methodology: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano.

Project administration: María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

Software: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano.

Validation: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

Visualization: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

Writing – original draft: Jonathan Martínez-Líbano, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

Writing – review and

editing: María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera.

ANNEX 1

Scale of the Fear of Funas in Social Networks (FFSN)

Instructions

From your experience in the last month related to fear of funa in social networks:

Below are a series of statements describing different feelings and perceptions about funas. Please indicate how much you agree with these statements using the following scale: 1. Strongly Disagree; 2. Disagree; 3. Neither Disagree nor Agree; 4. Agree; and 5. Strongly Disagree. Select this option if the statement describes your experience perfectly or almost always. Answer each statement honestly and based on your own recent experience. There are no "right" or "wrong" answers. Your opinion is what counts.

|

# |

Factor |

Item |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1 |

AFFSN |

When I see a funa on social networks, I think about what I would do if it were me. |

|||||

|

2 |

FCFSN |

I think that if I were to be the target of a funa, it would profoundly affect my life. |

|||||

|

3 |

AFFSN |

I get anxious when I think about someone posting something that affects my honor or image on social networks. |

|||||

|

4 |

AFFSN |

When I think that someone might make me a target of a funa, I get a stomach ache. |

|||||

|

5 |

FCFSN |

If I were to be a target of funa, it would be tough to cope with it. |

|||||

|

6 |

AFFSN |

I have been afraid that someone might make me the target of a funa on social networks. |

|||||

|

7 |

AFFSN |

Thinking that someone might make me the funa target makes me anxious. |

|||||

|

8 |

AFFSN |

Sometimes, I avoid conflicts just because I fear being made the target of a funa. |

|||||

|

9 |

FCFSN |

I would lose my loved ones if I were to be made the target of a funa. |

|||||

|

Factors: AFFSN = Anxiety Facing Funas in Social Networks; FCFSN = Fear of the Consequences of Funas in Social Networks |

|||||||

|

Correction |

Add up all the scores directly |

|

Interpretation |

Rank 9 to 15: Low fear of funas on social networks. |

|

Rank 16 to 30: Medium fear of funas on social networks. |

|

|

Rank 31 to 45: High fear of funas on social networks. |