doi: 10.56294/saludcyt20241151

ORIGINAL

Wellness Perception and Spiritual Wellness Practices of women of the Irula Tribe of the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve, India

Percepción del bienestar y prácticas de bienestar espiritual de las mujeres de la Tribu Irula de la Reserva de la Biosfera de Nilgiris, India

Geetha Veliah1

![]() *, Padma

Venkatasubramanian2

*, Padma

Venkatasubramanian2 ![]() *

*

1School of Public Health, SRM Institute of Science and Technology. Kattankulathur, Chengalpattu - 603203, India.

2School of Health Sciences and Technology, UPES. Dehradun, India.

Cite as: Veliah G, Venkatasubramanian P. Wellness Perception and Spiritual Wellness Practices of women of the Irula Tribe of the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve, India. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024; 4:1151. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt20241151

Submitted: 31-01-2024 Revised: 04-04-2024 Accepted: 18-07-2024 Published: 19-07-2024

Editor: Dr. William

Castillo-González

![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: spiritual Wellness promotion is primordial at a fundamental level. For Indigenous Peoples across the world spiritual wellness is their way of life. In India we have many traditional and tribal communities that practice a holistic, nature-centric spiritual wellness. Towards learning more about Indigenous communities and their spiritual wellness conducted this exploratory study among the Irulas of the Nilgiris District in Tamil Nadu India. Being one of earlier settlers of the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve, the Irulas have played an important role in the maintenance of the forests and environment of the Nilgiris.

Methods: the study design is an ethnography qualitative study using In-depth interviews conducted using Dr. Kovach’s Conversation methodology for researching and documenting Indigenous Ontology. The Indigenous peoples are one of the Primitive Tribes of the Nilgiris District in Southern India known as the Irulas. The settlements that were accessed for the interview include villages in the eastern and western slopes of the Nilgiris.

Results: using basic qualitative analysis of coding and theme generation, data allowed to derive 4 themes about spiritual wellness namely: What is Spirituality, Importance of participation, Sustaining Practices and Conviction. There is a shift and adaptation to contemporary spiritual practices driven by lack of access to their forests and grasslands and also because of education and exposure of the younger generation.

Conclusion: development over time has resulted in changes in their natural environment as well as social environment leading to generational perception and practices of spirituality among women of the Irula tribes of the Nilgiris.

Keywords: Spiritual Wellness; Indigenous Peoples; Irulas; Nilgiris.

RESUMEN

Introduction: la promoción del bienestar espiritual es primordial a un nivel fundamental. Para los pueblos indígenas de todo el mundo, el bienestar espiritual es su forma de vida. En la India hay muchas comunidades tradicionales y tribales que practican un bienestar espiritual holístico y centrado en la naturaleza. Con el fin de conocer mejor las comunidades indígenas y su bienestar espiritual, hemos realizado este estudio exploratorio entre los irulas del distrito de Nilgiris, en Tamil Nadu (India). Como uno de los primeros pobladores de la Reserva de la Biosfera de Nilgiris, los irulas han desempeñado un papel importante en el mantenimiento de los bosques y el medio ambiente de Nilgiris.

Métodos: el diseño del estudio es un estudio cualitativo etnográfico mediante entrevistas en profundidad realizadas utilizando la metodología de conversación del Dr. Kovach para investigar y documentar la ontología indígena. Los indígenas son una de las tribus primitivas del distrito de Nilgiris, en el sur de la India, conocidos

como los Irulas. Los asentamientos a los que se accedió para la entrevista incluyen aldeas en las laderas oriental y occidental de los Nilgiris.

Métodos: el diseño del estudio es un estudio cualitativo etnográfico mediante entrevistas en profundidad realizadas utilizando la metodología de conversación del Dr. Kovach para investigar y documentar la ontología indígena. Los indígenas son una de las tribus primitivas del distrito de Nilgiris, en el sur de la India, conocidos como los Irulas. Los asentamientos a los que se accedió para la entrevista incluyen aldeas en las laderas oriental y occidental de los Nilgiris.

Resultados: utilizando un análisis cualitativo básico de codificación y generación de temas, los datos permitieron derivar 4 temas sobre el bienestar espiritual a saber: Qué es la espiritualidad, Importancia de la participación, Prácticas sostenibles y Convicción. Existe un cambio y una adaptación a las prácticas espirituales contemporáneas debido a la falta de acceso a sus bosques y praderas y también a la educación y la exposición de la generación más joven.

Conclusiones: el desarrollo a lo largo del tiempo ha provocado cambios en su entorno natural, así como en su entorno social, lo que ha dado lugar a una percepción y unas prácticas generacionales de la espiritualidad entre las mujeres de las tribus irula de los Nilgiris.

Palabras clave: Bienestar Espiritual; Pueblos Indígenas; Irulas; Nilgiris.

INTRODUCTION

Wellness as a state can be defined as a holistic and dynamic condition characterized by physical, mental, and social well-being. It encompasses a proactive approach to living that promotes health and fulfilment across various dimensions of life.(1) Wellness as a state is dynamic, requiring active engagement and continuous effort to achieve and maintain balance across its various dimensions. It is where individuals take responsibility for their well-being, making informed choices and adopting behaviors that promote overall health and quality of life.(2)

Indigenous wellness is a comprehensive and integrative approach that emphasizes the interconnection of physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health. It is deeply rooted in cultural traditions, community connections, and a profound connection to the land.(3) While indigenous peoples face significant challenges to their wellness, their resilience and strength are evident in their ongoing efforts to preserve and revitalize their cultures and communities.

Promotion of spiritual wellness post-pandemic is prudent practice. Spiritual Wellness provides insights into how spiritual beliefs and practices influence mental, emotional, physical, and social health.(4) Furthermore, Understanding and addressing spiritual wellness is crucial for fostering resilience, enhancing recovery, and ensuring cultural competence in healthcare and public health initiatives.

The purpose of this study is to document the wellness and spiritual wellness practices of these indigenous tribes. While there is existing documentation of their practices before independence, this study aims to capture additional aspects of wellness that have emerged post-independence. For posterity it is important to record these ancient knowledge practices since they can support and maintain wellness when combined with new healthcare requirements. We will be recording the wellness habits and perceptions of the Irula women in the Nilgiris District through this exploratory qualitative study.

METHOD

Study Design: ethnographical qualitative study.

Time Period: the researcher spent over 3 weeks of cumulative time during July 2022 – October 2023 and with due approval from the State Government, Local NGO approval to conduct the study. This study was approved by the SRM Medical College and Research Centre Ethics committee and the approval number for the study was # 2912/IEC/2021.

Participant selection: participants in this study were drawn from the Irula tribal group residing in the Nilgiri District. For logistical convenience and to ensure representation of distinct Irula settlements, the Kotagiri Taluk and Coonoor Taluk were selected due to their accessibility. Fourteen revenue villages in Kotagiri Taluk and seven in Coonoor Taluk are inhabited by Irulas; among these, the villages of Kotagiri and Berliar were specifically chosen for the study. Within these villages, the Kunjapanai and Burliar Irula settlements were included.(5) Six Women from these settlements were randomly selected for in depth interviews to ensure unbiased sampling.

Interview Method: indigenous knowledge represents a unique way of knowing, rooted in the oral tradition of sharing wisdom. This method is often referred to by Indigenous researchers worldwide as storytelling, yarning, talk story, re-storying, and re-membering.(6) (7) (8) We used Kovach’s conversation as the methodology to elicit our information for the research.(9) The conversational method holds significant importance in Indigenous methodologies because it aligns with the oral storytelling tradition, a fundamental aspect of the Indigenous paradigm for gathering knowledge.

Interview Tool: an in-depth interview guide was developed based on literature review on Wellness and Wellbeing. This guide serves as a probing tool to ensure the comprehensive coverage of wellness indicators. The various domains that were explored included 1) Physical 2) Mental 3) Social 4) Spiritual 5) Environmental and 6) Occupational wellness.

|

Table 1. Location of the Study Sample |

|||||

|

S. No |

Name of the Taluks |

Name of the Revenue Village |

Name of the Irula Settlements |

Number of Families |

Total Population |

|

1. |

Coonoor |

Berliar |

Burliar |

18 |

86 |

|

2. |

Kotagiri |

Kotagiri |

Kunjapanai |

45 |

221 |

Analysis

Data Analysis: constituted multiple steps –

Data organization: data was organized in MS Excel, by populating tribe wise, and respondent wise sentences and words in rows and columns for systematic analysis.

Coding: Key words and phrases were identified and coded to facilitate thematic analysis.

Identification of Themes: Common themes were identified from the coded data.

Building Categories: themes were grouped into broader categories to provide a structured sense of the data.

Synthesis and Reporting: the last step involved synthesizing the findings and reporting them. This included data interpretation, inference, and providing recommendations based on the research objectives.

This methodological flow enabled a comprehensive and ethical exploration of wellness and well-being among the Adivasis.

RESULTS

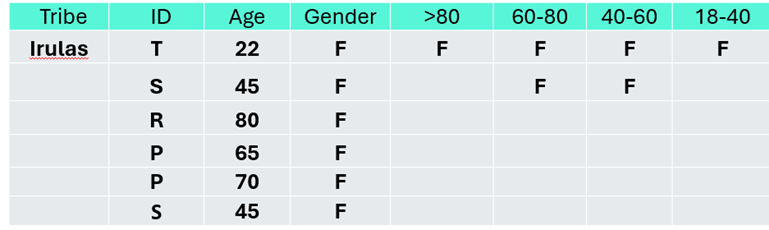

The demographic spread of our study participants is as follows: a 22-year-old, two women 45, one 65 years, one 70 years and one woman 80 years of age. Except for the 22-year-old, the rest of them had less than grade 5 education.

Figure 1. Distribution of Sample - By Age

Perception about wellness domains:

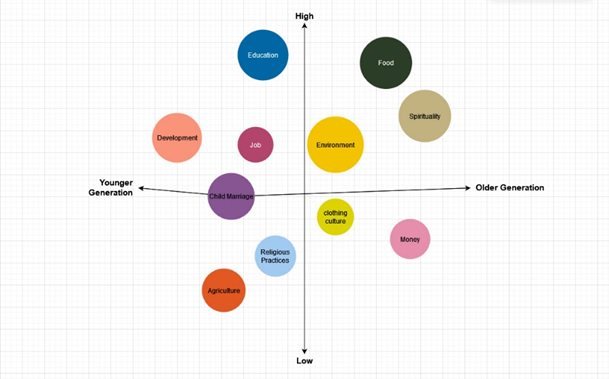

Perceptions varied with age, in the figure above the Y axis depicts the importance from Low to high and the X axis, age. The size of the circle depends on the number of responses from the people interviewed for this research.

Education was rated high by all of the women and strongly emphasized by the younger women (>18-50-year-olds. However, the younger women prioritized development more than others, while middle-aged women identified livelihood (job) as important. The younger generations emphasized social norms like child marriages and endogamy more than other domains, while the older generations ranked money lower than other domains. Among the older generation domains that mattered were environment, spirituality, and healthy food, while clothing and culture, in a few aspects, did not have the same level of importance.

Overall, wellness practices among the women reveals an evolving landscape. The domains that are highlighted as important for wellness by the Irula women include 1) Education 2) Environment 3) Livelihood 4) Spirituality 5) Food 6) Values and Respect

Spiritual Wellness:

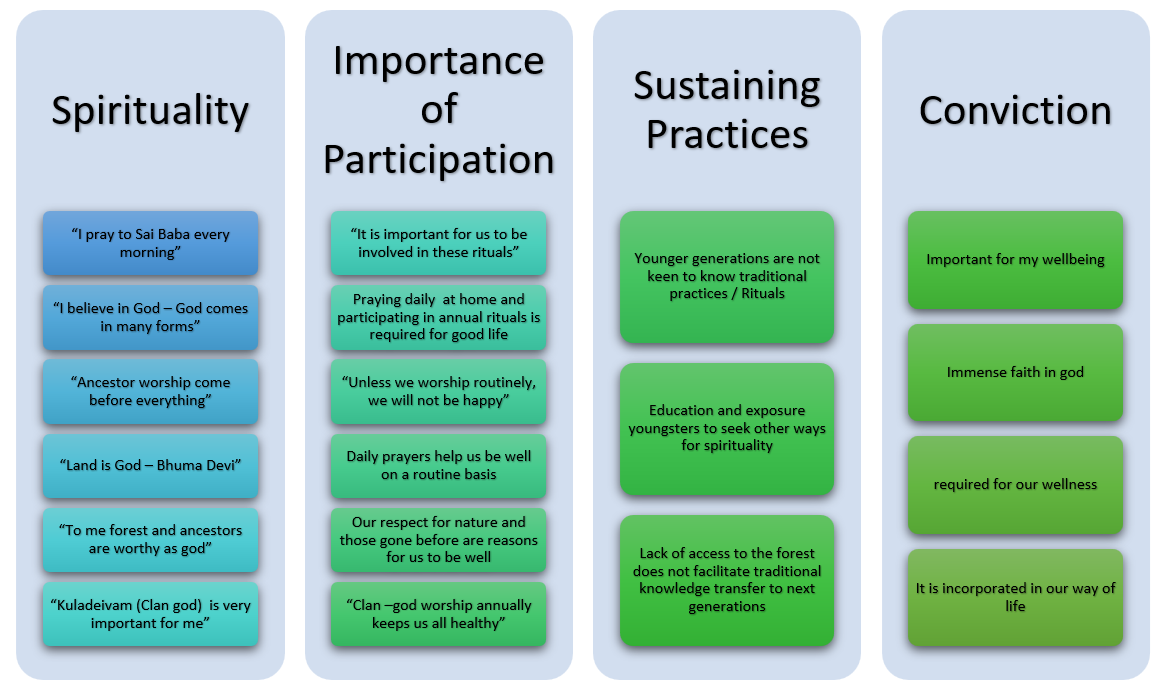

We derived themes about spirituality as a wellness domain, including its definition, the significance of participation, sustainable practices, and the respondents’ convictions. Figure 2 below describes Spirituality as wellness domain and themes that were derived namely, what is spirituality, Importance of Participation, Sustaining practices and Conviction from the respondents.

Figure 2. Perception Map of Wellness

Figure 3. Spiritual Wellness Themes

Theme 1: what is Spirituality to you: the youngest of the respondents reported praying to mainstream god “Sai Baba” while others responded with god being in many forms, to ancestor worship being part of their understand of spirituality, In particular, a middle aged Irula woman responded by saying that their land is god (Bhooma devi), an older Irula woman connected her spirituality to the forest as well as her ancestors while another older respondent spoke about her “clan” god and that everyone has one that is important to be prayed to.

Theme 2: Understanding the importance of participation in Rituals: all respondents acknowledged the significance of traditional prayers and rituals, albeit with varying motivations. The youngest respondents emphasized the importance of participating in these rituals to pass them on to future generations, while the middle-aged respondents associated these rituals, such as home, annual, and ancestor worship, with a good life, happiness, and health.

Theme 3: Sustaining Practice: being intricately involved in Tribal wellness, transfer of knowledge about tribal culture and spirituality becomes imperative. The women in their responses had these observations about sustaining this practice: lack of access to the forest has impeded transfer of traditional rituals since the Irulas for generations have been tying their spiritual and belief in God to their land and forests. Furthermore, education and exposure has allowed younger people to explore other ways of worship. Also, being in school and college does not allow the younger people to be engaged in these rituals and hence there is less interest further compounded by the lack of access to the forest where many of these rituals happen traditionally.

Theme 4: Conviction: the comparable words that were used to highlight their conviction about spirituality includes – Important, Immense faith, equated to wellness, and incorporated as a way of life for them. These words portray the level of belief in spirituality, rituals and worship practices. Universally all the women interviewed had beliefs however there were differences in perception with three of the six women interviewed eluded to spirituality being a way of life and that is was pervasive in all their activities by using terms like equated to wellness, incorporated as a way of life /living.

DISCUSSION

Tribal people have a profound sense of respect, humility, and reciprocity through their deep spiritual connection to Mother Earth. This ethos is rooted in thousands of years of subsistence practices and values. Their way of life, including hunting, gathering, and fishing, is centered around providing for oneself, family, the elderly, the community, and for ceremonial purposes. They adhere to the principle of taking only what is needed and being mindful of how much they take and use, ensuring that future generations are not put at risk (10).

The Irulas, an indigenous tribe of the Nilgiri District, have a rich spiritual heritage deeply intertwined with their natural surroundings and cultural traditions. Their spiritual practices reflect a harmonious relationship with nature and a profound respect for ancestral and local deities. According to C.P. Vinod, an Irula life is totally religion oriented. (11) In all affairs they seek the permission of their clan deities. Many of the Irulas in recent times have adapted to worshipping Hindu Gods and Goddess and religious practices as well. Anecdotal data indicates that many older generation Irula women feel that because of not praying to their ancestor and clan gods has resulted in the tough times that they face consistently. However, this belief is not carried on to the younger generations. This also can be attributed to the fact that there are mixed marriages, Irulas marrying other Tamil communities where the worship and spirituality is different.

Irulas in the past were Nature Worshippers which was brought out by the older respondents in this research by equating forest and land to God. Certain groves and trees are considered sacred and are sites for rituals and offerings. (12) These natural sanctuaries are believed to be the abodes of spirits and deities. Access to the groves and forest now are restricted due to the area being considered Reserve Forests and due to changes in the forests there is a lot more wild animals which restrict the movement of the tribes with ease and safety hampering the transfer of cultural and traditional heritage to the younger generations. (13)

As important as Nature was ancestral worship, many of the respondents indicated that fact. The Irulas pay homage to their ancestors, believing that the spirits of their forebears watch over them and influence their daily lives. Rituals and ceremonies are integral to Irula spiritual life, marking important agricultural cycles, life events, and seasonal changes. (14) All these rituals are learned being an oral and observation-oriented transfer of knowledge through festivals. Festivals are significant occasions for communal worship and celebration, reinforcing social bonds and cultural identity. (15) Anecdotal evidence during this research study alluded to women talking with the trees and that they can communicate with the trees. This is critical in understanding how sacred and sanctified their environment is considered by the tribes. (16)

In the larger scheme of health and wellness, spirituality plays a major role in mental health among the tribes. (17) A stronger conviction in connection to a higher power helps alleviate the challenges of mental stress. This is achieved through their bond with nature and rituals that link the community with nature and their deities.

With changing times and priorities of the Irulas, there are multiple challenges in handing down practices that are crucial to the identity of the tribes. These practices provide a sense of identity, continuity, and resilience, enabling the Irulas to navigate the complexities of the modern world while remaining rooted in their ancestral wisdom and natural environment.

Conclusion: Spirituality as a dimension of wellness is fundamental to the Irulas’ overall health and well-being. By consultative process we need to revitalize traditional practices by providing access to the forests and integrating spiritual wellness practice through schools as well. This approach not only benefits individual Irulas but also strengthens community resilience and social cohesion, leading to healthier and more empowered communities. Recognizing the spiritual dimension of wellness is essential for achieving inclusive and effective health outcomes for the Irulas.

REFERENCES

1. Kirsten, Van Der Walt H, Viljoen C. Health, well-being and wellness: An anthropological eco-systemic approach. Health SA Gesondheid. 2009;14:1–7.

2. Redland AR, Stuifbergen AK. STRATEGIES FOR MAINTENANCE OF HEALTH-PROMOTING BEHAVIORS. Nursing Clinics of North America [Internet]. 1993 Jun 1;28(2):427–42. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0029646522028717?via%3Dihub.

3. Marques B, Freeman C, Carter L, Zari MP. Conceptualising therapeutic environments through culture, Indigenous knowledge and landscape for health and well-being. Sustainability. 2021;13:9125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169125.

4. Oman D, Thoresen CE. Do religion and spirituality influence health. In: Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2005. p. 435-59.

5. Parthasarthy J. Irulas of Nilgiri District, Tamil Nadu. Tribal Research Centre (TRC). 2013.

6. Absolon K, Willett C. Aboriginal research: Berry picking and hunting in the 21st century. First Peoples Child Fam Rev. 2004;1(1):5-17.

7. Bishop R. Collaborative storytelling: Meeting Indigenous people’s desires for self-determination. Paper presented at the World Indigenous People’s Conference, Albuquerque, New Mexico, June 15-22, 1999.

8. Wilson S. What is an Indigenous research methodology? Can J Native Educ. 2001;25(2).

9. Kovach M. Conversation method in Indigenous research. First Peoples Child Fam Rev. 2010;5(1):40–48. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069060ar.

10. Portrayal of tribal life in Indian movie and Indian novel: An ecocritical study. J Pharm Negat Results [Internet]. 2022 Dec. 31 [cited 2024 Jun. 23]:9130-7. Available from: https://pnrjournal.com/index.php/home/article/view/6488.

11. Vinod CP. An ethnographic report on the Alu Kurumbas. Internation School of Dravidian Linguistics, Thiruvananthapuram.

12. Rameshkumar M. Kanniyamman worship of Irulas. Shanlax Int J Tamil Res (Online). 2022;6:46–52. https://doi.org/10.34293/tamil.v6i3.4623.

13. Francis W. The Nilgiris. Madras District Gazetteer. 1908. Government Press Madras.

14. R NSK, Kasi E. Continuity and change of folklore among Irulas of Kerala: Discourse analysis of tribal folk songs from the South Indian State of India. Contemp Voice Dalit. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455328x231223050.

15. Rajankar P, Gandhi MP. The Irula Tribe. Available from: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/50769454/irula_final-libre.pdf.

16. Kakoty S. Ecology, sustainability and traditional wisdom. J Clean Prod. 2018 Jan 20;172:3215-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.036.

17. Bhasin V. Medical anthropology: a review. Studies on Ethno-medicine. 2007 Jan 1;1(1):1-20.

FINANCING

The authors did not receive financing for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Geetha K. Veliah.

Data curation: Geetha K. Veliah.

Formal analysis: Geetha K. Veliah.

Research: Geetha K. Veliah.

Methodology: Geetha K. Veliah and Padma Venkatasubramanian.

Project management: Geetha K. Veliah and Padma Venkatasubramanian.

Resources: Geetha K. Veliah and Padma Venkatasubramanian.

Software: Geetha K. Veliah and Padma Venkatasubramanian.

Supervision: Padma Venkatasubramanian.

Validation: Geetha K. Veliah and Padma Venkatasubramanian.

Display: Geetha K. Veliah.

Drafting - original draft: Geetha K. Veliah and Padma Venkatasubramanian.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Geetha K. Veliah and Padma Venkatasubramanian.