doi: 10.56294/saludcyt2024.1025

ORIGINAL

Qualitative Study: Nursing Managers in Managing Nurse Educators in Hospitals

Estudio cualitativo: los directores de enfermería en la gestión de docentes de enfermería en hospitales

Cicilia Ika Wulandari1,2 ![]() *, Hanny Handiyani3

*, Hanny Handiyani3 ![]() *, Enie Novieastari3

*, Enie Novieastari3 ![]() *, Diantha Soemantri4

*, Diantha Soemantri4 ![]() *, Ichsan Rizany1,5

*, Ichsan Rizany1,5 ![]() *

*

1Doctoral program in nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Depok, Indonesia.

2 Nursing Science Program, Sint Carolus School of Health Sciences, Jakarta, Indonesia.

3Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Department Fundamental of Nursing. Depok, Indonesia.

4Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Department of Medical Education. Depok, Indonesia.

5Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, Lambung Mangkurat University, Department Nursing Management. Banjarbaru, Indonesia.

Cite as: Wulandari CI, Handiyani H, Novieastari E, Soemantri D, Rizany I. Qualitative Study: Nursing Managers in Managing Nurse Educators in Hospitals. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024; 4:.1025. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024.1025

Submitted: 28-02-2024 Revised: 23-05-2024 Accepted: 09-10-2024 Published: 10-10-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

Corresponding author: Hanny Handiyani *

ABSTRACT

Introduction: nurse managers are responsible for managing human resources, including nurse educators in hospitals. Although nurse educators are professionals, there is limited knowledge about the competencies required for their roles within hospital programs. This study aims to analyze the experiences of nursing managers in managing nurse educators in hospitals.

Method: this research employs a qualitative design using a phenomenological approach. The study was conducted in two hospitals, utilizing purposive sampling based on predetermined inclusion criteria. The participants included nine nurse managers responsible for the nurse educator program, each having served for at least three years. In-depth interviews were conducted, and the collected data were subjected to thematic analysis.

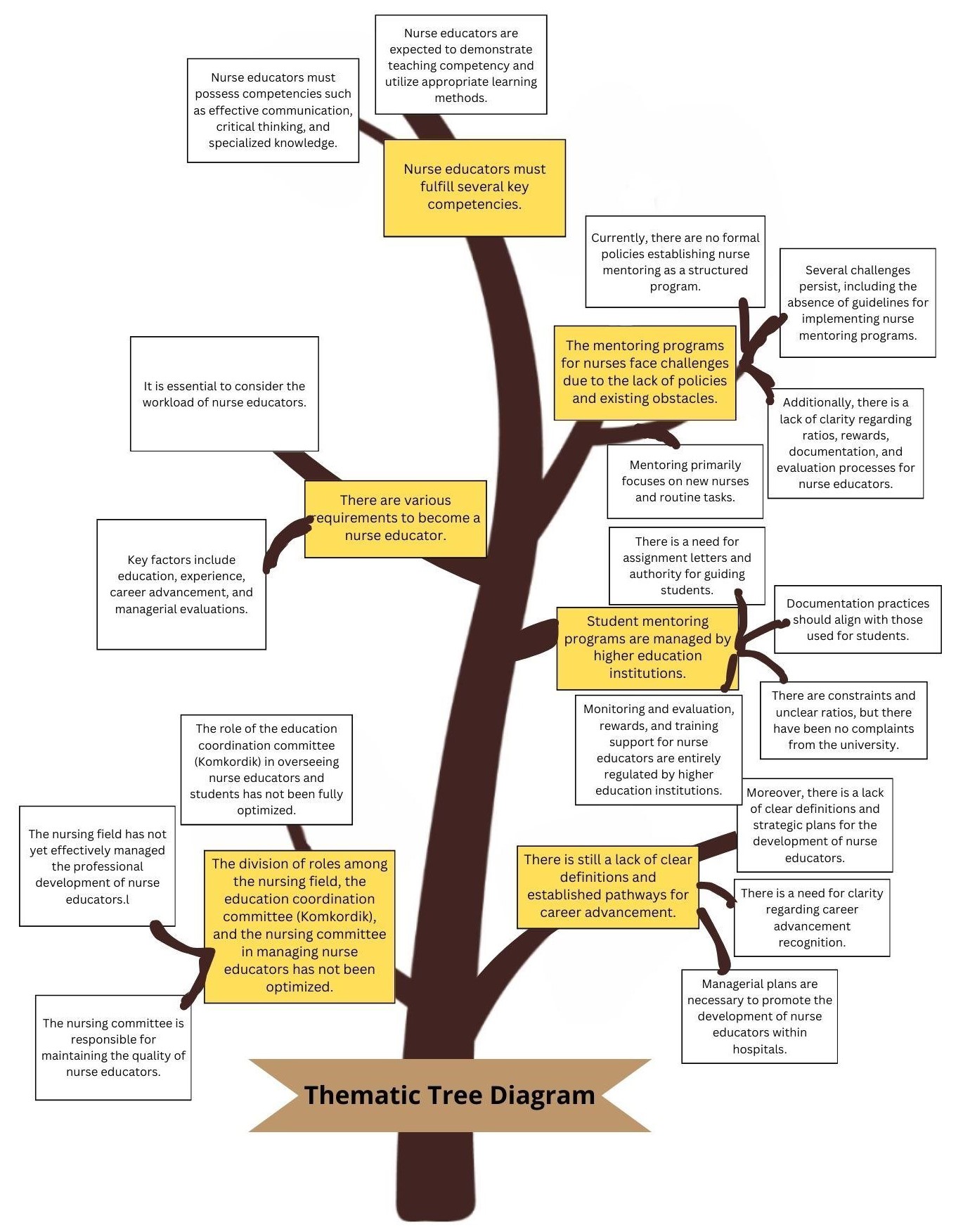

Results: the study identified six themes: 1) The suboptimal division of roles among nursing fields, the Education Coordination Committee (Komkordik), and the nursing committee in managing nurse educators; 2) Various requirements for becoming a nurse educator; 3) The competencies that nurse educators must fulfill; 4) The inadequacy of the mentoring program for nurses due to the lack of policies and existing challenges; 5) The management of student mentoring programs by higher education institutions; 6) The absence of definitions and career pathways for nurse educators.

Conclusion: the findings indicate that nursing managers, as supervisors of nurse educators, possess unique experiences and require clearer definitions of the role of nurse educators along with regulations for their career advancement.

Keywords: Hospitals; Nurse Manager; Nurse Educator; Professional Competence.

RESUMEN

Introducción: los gerentes de enfermería son responsables de gestionar los recursos humanos, incluidos los educadores de enfermería en los hospitales. Aunque los educadores de enfermería son profesionales, existe un conocimiento limitado sobre las competencias requeridas para sus roles dentro de los programas hospitalarios. Este estudio tiene como objetivo analizar las experiencias de los gerentes de enfermería en la gestión de educadores de enfermería en hospitales.

Método: esta investigación emplea un diseño cualitativo utilizando un enfoque fenomenológico. El estudio se llevó a cabo en dos hospitales, utilizando un muestreo intencional basado en criterios de inclusión predeterminados. Los participantes incluyeron nueve gerentes de enfermería responsables del programa de educadores de enfermería, cada uno de los cuales había trabajado durante al menos tres años. Se realizaron entrevistas en profundidad y los datos recopilados se sometieron a un análisis temático.

Resultados: el estudio identificó seis temas: 1) La división subóptima de roles entre los campos de enfermería, el Comité de Coordinación de Educación (Komkordik) y el comité de enfermería en la gestión de educadores de enfermería; 2) Varios requisitos para convertirse en un educador de enfermería; 3) Las competencias que deben cumplir los educadores de enfermería; 4) La insuficiencia del programa de tutoría para enfermeras debido a la falta de políticas y desafíos existentes; 5) La gestión de los programas de tutoría estudiantil por parte de las instituciones de educación superior; 6) La ausencia de definiciones y trayectorias profesionales para los educadores de enfermería.

Conclusión: los hallazgos indican que los gerentes de enfermería, como supervisores de los educadores de enfermería, poseen experiencias únicas y requieren definiciones más claras del papel de los educadores de enfermería junto con regulaciones para su avance profesional.

Palabras clave: Competencia Profesional; Enfermera Jefa; Enfermera Educadora; Hospitales.

INTRODUCTION

The roles and responsibilities of nurse managers are both complex and vital for ensuring high-quality care in hospitals. Nurse managers are responsible for effectively managing nursing resources.(1) Poor management of these resources can compromise patient care quality.(2) This complexity also encompasses the management of nurse educators within hospital settings.

Nurses involved in mentoring or educating colleagues or students are assigned various titles that reflect their specific roles. The term “preceptor” is designated for nurses who train new staff and students. When the mentee is a more experienced nurse, they are referred to as a “mentor”.(3) Some individuals use the title “clinical instructor”.(4) Traditionally, clinical educators have focused primarily on students.(5,6) In Indonesia, the roles and competencies of nurses engaged in the education of peers or students remain ambiguous, which has led to the introduction of the term “nurse educator.” However, the definition of nurse educators in Indonesia lacks clarity, and there is limited research addressing this topic.

Nurse educators play a crucial role in maintaining the quality of care, but this quality is not consistently achieved. This highlights the importance of nurses’ contributions to healthcare delivery within hospitals. Nurses also act as educators to improve the knowledge base of both their peers and students.(7) Nurse educators support nurses and students in delivering high-quality care.(8,9) However, nurse managers often choose nurses for educational roles based more on their willingness than their qualifications.(10) Many nurse educators feel unprepared for teaching and have difficulty identifying relevant information that is straightforward to communicate. They frequently express feelings of unpreparedness for their teaching responsibilities and lack sufficient time for staff development.(11,12) Additionally, nurses feel that their roles and additional competencies as educators are not sufficiently acknowledged.(13) These factors impede the effective functioning of nurses in their educational capacities.

The significance of nurse educators presents unique challenges for nurse managers in hospitals. Effectively coordinating the work of nurse educators is a considerable challenge that is not easily addressed. Previous research indicates that hospital managers have not fully provided the necessary resources and support for fulfilling their responsibilities.(11,12) Earlier studies have not explored the specific role of managers in overseeing nurse educators in depth. Additionally, there is a disconnect between government regulations and the practical implementation of nurse educator roles, which warrants further investigation from the perspective of hospital managers. This study aims to analyze the experiences of nursing managers in managing nurse educators within hospital settings.

METHOD

Design

The research adopted a qualitative design utilizing a phenomenological approach. Phenomenology aims to explore the underlying facts of a social phenomenon, focusing on understanding human behavior from the informant’s perspective.(14) This methodology is designed to analyze and convey data obtained through in-depth interviews. The authenticity of the experiences presented in this study is grounded in the real-life situations faced by nurses who oversee nurse educators in hospital settings. The study was conducted at RSUP Persahabatan in Jakarta and the University of Indonesia Hospital in West Java.

Participants were selected using maximum variation sampling, taking into account factors such as age, education, experience, and career level. Data collection occurred between March and June 2024, involving a total of nine participants. The criteria for inclusion were: (1) at least three years of experience as a nurse manager or supervisor of nurse educators; (2) possession of a master’s degree in nursing; and (3) the ability to effectively articulate their experiences. The exclusion criteria were respondents who were on leave or sick during the research period. In this study, there were no participants who were included in the exclusion criteria.

Data Collection

In-depth interviews were utilized in this research, which effectively elicited detailed responses from participants. The interviews were guided by a set of predetermined questions. During the data collection phase, the researcher employed bracketing, a process that involves setting aside assumptions, beliefs, and prior knowledge regarding nurse education.(15,16) The interview guide included several open-ended questions aimed at encouraging participant engagement, such as: 1) What has been your experience in managing nurse educators? 2) How can the competencies of nurse educators be improved? 3) How is recognition provided to nurse educators? 4) What challenges and opportunities do you perceive in managing nurse educators? 5) What are your thoughts on the PMK career pathways for nurse educators? Each interview lasted between 60 to 90 minutes. The researcher employed an interview guide, a voice recorder, and field notes. Before data collection, participants received a thorough overview of the study’s key components, including the recording equipment, the purpose and benefits of the research, and the anticipated duration of the study.

Ethical Considerations

The researcher is committed to upholding three fundamental rights of participants: respecting their dignity, prioritizing their well-being, and ensuring fairness for all individuals involved.(16) Participants cultivated a trusting relationship and arranged meeting times via WhatsApp. During in-person meetings, they were informed about the study’s objectives and the interview process. It was clearly stated that participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any point before the results were published. Written consent to participate in the research was obtained after the researcher met with each participant directly. The researcher assured that the confidentiality of all participants would be maintained. Ethical approval for this study was granted by RSUPP (Ref: 0019/KEPK-RSUPP/01/2024) and RSUI (Ref: S-013/KERLIT/RSUI/I/2024).

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using thematic analysis, following the steps outlined by Colaizzi. The researcher conducted a thorough, word-by-word examination of the data, followed by multiple careful readings. The thematic analysis continued with the creation of codes based on key statements. Subsequently, the researcher identified subcategories and overarching themes. The resulting data were continuously compared using a constant comparative method.(17) This iterative process enabled the identification of meanings and the development of comprehensive themes. The study adhered to principles of data validity, including credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability. The themes were visually represented as a thematic tree.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Respondents

Participants in this study were individuals in charge of the nurse educator program at hospitals. The study included nine participants from two different hospitals, consisting of five females and four males. The ages of participants ranged from 33 to 57. Two participants held doctoral degrees, while the other seven had master’s degrees or specializations. Participants were employed in various units, including nursing, the nursing committee, and the Education Coordination Committee (Komkordik). Detailed characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. According to Table 1, 55,55 % of the participants were female, with the largest ethnic group being Javanese at 44,44 %. The levels on the career ladder varied from PK 3 to PK 5, with 77,77 % of the nurses holding a master’s degree in nursing, while the remaining participants had doctoral degrees in nursing.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of Respondents |

||

|

Characteristics |

n |

% |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Man |

4 |

44,44 % |

|

Woman |

5 |

55,55 % |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

Java |

4 |

44,44 % |

|

Sunda |

2 |

22,22 % |

|

Padang |

2 |

22,22 % |

|

Bugis |

1 |

11,11 % |

|

PK (Career Ladder) |

|

|

|

3 |

1 |

11,11 % |

|

4 |

3 |

44,44 % |

|

5 |

5 |

55,55 % |

|

Level Education |

|

|

|

Master of Nursing |

7 |

77,77 % |

|

Doctor of Nursing |

2 |

22,225 |

|

Source: Wulandari et al (2024) |

||

Thematic Findings

The identified themes are illustrated in a thematic diagram presented as a thematic tree (figure 1). This diagram visually represents the results of examining managerial experiences related to the oversight of the nurse educator program. The thematic analysis resulted in six comprehensive themes.

Suboptimal Role Distribution Among Nurse Managers, the Education Coordination Committee (Komkordik), and the Nursing Committee in Managing Nurse Educators

This theme consists of two subthemes, five categories, and eight codes. The first category emphasizes the roles of nurse managers and the Komkordik in regulating nurse educators, as reflected in a participant’s comment: “...during my time in the education and training division...” (P4). Another participant mentioned: “...RSUI functions as the Komkordik, but within the nursing sub-division...” (P5). The second category focuses on the Komkordik’s responsibilities for managing nurse educators and students at RSUI, with one participant stating: “...the Komkordik at RSUI falls under the RIK UI umbrella, which includes the medical sub-division, the medical committee, the nursing committee, the pharmacy sub-division, the public health faculty, and dentistry. Coincidentally, I am in the nursing sub-division...” (P5). Conversely, the third category indicates that the Komkordik at RSUPP does not oversee nursing education, as expressed by a participant: “...there are currently no nursing personnel within the Komkordik, despite it being an educational hospital. This might be a suggestion for the future...” (P2). The seventh category reveals that the nursing committee is responsible for managing career advancement, with one participant noting: “...to progress in our career ladder, we will request a presentation...” (P9).

Requirements for Becoming a Nurse Educator

This theme includes two subthemes and seven categories. The fourth category focuses on prioritizing nurse educators who receive favorable evaluations from management, as indicated by a participant’s statement: “...a clinical instructor (CI) who has frequently participated, even if they have undergone training, is preferred over those who have not...” (P5). The fifth category outlines the minimum educational requirements, stating that a bachelor’s degree (S1) is necessary for a CI with a D3 background, while a master’s degree (S2) is required for a CI with a bachelor’s degree: “...for a CI with a D3 background, the minimum requirement is a bachelor’s degree, and for a CI with a bachelor’s degree, the minimum requirement is a master’s degree...” (P1). The seventh category underscores the importance of work experience as an educator, ranging from five to over ten years, as articulated by a participant: “...having five years of experience in their specific role...” (P1).

Figure 1. Thematic Tree Diagram

Source: Wulandari et al (2024)

Competencies Required for Nurse Educators

This theme encompasses two subthemes and six categories. The first category emphasizes the importance of teaching and educational skills, as articulated by a participant: “...they can educate, teach, and guide; not everyone has the ability to educate, teach, and guide...” (P5). The fourth category focuses on effective communication skills and the capacity to influence others, highlighted by a participant’s remark: “...it’s about how they convey the message...” (P4). The sixth category underscores the necessity for specialized knowledge and the ability to integrate theory with practice, as expressed by a participant: “...applying theoretical concepts to real-world situations...” (P2).

Suboptimal Mentoring Programs for Nurses Due to Lack of Policies and Existing Challenges

This theme includes four subthemes and thirteen categories. The third category points out the absence of clear policies, guidelines, and assignment letters, as noted by a participant: “...our weakness is that we lack policies, so no one recognizes this as a nurse educator role...” (P3). The eighth category addresses the ambiguity regarding the nurse-to-nurse ratio, as explained by a participant: “...it’s not necessarily a 1 to 5 ratio like with students; for example, I might supervise three nurses for one month, and then the next month I’m still supervising those same individuals...” (P1). The eleventh category highlights the lack of clarity around evaluations and rewards for nurse educators, with a participant stating: “...we do not yet have support for clinical nurses and nurse educators...” (P1).

Student Mentoring Programs Managed by Higher Education Institutions

This theme consists of four subthemes and nine categories. The first category discusses the assignment letters for student mentors issued by the HEIs, as mentioned by a participant: “...the assignment letters for students come from there, perhaps from their end...” (P7). The fifth category reveals that there have been no complaints from the HEIs, as expressed by a participant: “...there are no complaints...” (P2). The ninth category addresses the rewards and training support provided by the HEIs, with a participant noting: “...the honorarium is paid by the faculty, not by the hospital...” (P4).

Lack of Definition for Nurse Educators and Career Advancement

This theme is composed of three subthemes and twelve categories. The first category highlights the diverse definitions of nurse educators, as articulated by a participant: “...during clinical teaching, one is an instructor... actually, a mentor is more akin to a preceptor, but it’s not structured; if the preceptor is appointed, then they have a defined role, but a mentor’s role is not...” (P7). The second category addresses the lack of a strategic plan for developing nurse educators: “...we are just starting this initiative, and no one has taken the lead to oversee it, so we have yet to make any progress...” (P3). The fourth category reveals that support for development and rewards is not yet apparent: “...while some allowances have been implemented, many have not received them due to budget constraints...” (P1). The fifth category reflects the aspirations of nurse managers for recognition and regulatory frameworks to facilitate career advancement: “...there should be rewards from the Ministry of Health to acknowledge clinical instructors (CIs), which would enhance their confidence and recognition...” (P1). The sixth category emphasizes that nurse managers assist nurses in obtaining their Nurse Registration Number (NIDK), as noted by a participant: “...having an NIDK adds significant value during accreditation...” (P1).

DISCUSSION

Suboptimal Role Distribution Among Nurse Managers, the Education Coordination Committee (Komkordik), and the Nursing Committee in Managing Nurse Educators

The role of nurse managers in overseeing nurse educators is critical. Research indicates that nurse managers are expected to have skills in human resource management, which includes managing nurse educators.(18) However, studies show that many nurse managers lack strategic plans for the professional development of nurses. Instead, they often focus solely on the individual needs of nurses during professional development activities.(2) While the Komkordik is also responsible for managing nurse educators, in some hospitals, it does not oversee nursing education. This situation contrasts with findings that suggest the Komkordik acts as a liaison between clinical educators in hospitals and educational institutions. Additionally, nursing committees within hospitals are responsible for credentialing nurses to improve their competencies.(19) The individual in charge of nurse educators plays a crucial role in preparing nurses for their jobs and ensuring patient safety.(20) Research indicates that nurse managers often do not fully understand the role of nurse educators, which impacts the resources available for them to perform their duties effectively.(21,22) Consequently, nurse educators are not fully able to fulfill their educational responsibilities.(11) It is essential to clarify the roles of nurse managers, the Komkordik, and the nursing committee in managing nurse educators to avoid overlapping responsibilities.

Requirements to Become a Nurse Educator

Nurse managers play a vital role in shaping the competencies of nurse educators, either by enhancing or hindering their development. The evaluation of a nurse’s competence by managers can vary based on several factors, including age, work experience, education, personal characteristics, clinical context, organizational dynamics, and the overall culture of care.(23) A fundamental requirement for becoming a nurse educator is a combination of education and relevant work experience. Research shows that in Australia, nurse educators are registered nurses who train other nurses and do not need to undergo a credentialing process; they simply need to hold a higher degree to teach nurses at lower levels.(24) In contrast, nurse educators in the United States must enhance their teaching competencies through formal education and are expected to engage in research and evidence-based practice. It is crucial for nursing managers to implement workforce functions that encompass (1) human resource planning, (2) selection, (3) utilization of nurses according to their competencies, (4) oversight, and (5) staff development. One important aspect of developing nurse educators involves setting appropriate requirements for clinical educators within hospitals.

Competencies Required for Nurse Educators

Nurse educators are expected to possess specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are essential for effective teaching. Knowledge is a core component of a nurse educator’s competency, and they must have a strong foundation in research. Nurse educators are instrumental in applying this knowledge to integrate evidence-based practice into their teaching.(25,26) Moreover, they should have a thorough understanding of complex cases that arise within nursing curricula. Research supports the idea that nurse educators should embrace a holistic approach to nursing care.(27) Additionally, effective teaching is a crucial expectation for nurse educators. Teaching efficacy, defined as the belief in one’s ability to teach successfully, is a key element in the educator’s role. This efficacy influences their capability to impart knowledge to others,(28) and is essential for achieving effective learning outcomes.(29) Nurses who exhibit strong teaching efficacy are more receptive to new ideas, create supportive learning environments, and demonstrate persistence in their teaching efforts. As managers, all nurses are expected to communicate effectively and manage various aspects such as information technology, finance, human resources, business strategies, and organizational operations. The right teaching competencies are anticipated to empower nurse educators in successfully fulfilling their roles.

Suboptimal Mentoring Programs for Nurses Due to Lack of Policies and Existing Challenges

Although regulations governing nurse educators are in place, there is still a lack of detailed clarity regarding the competencies required for these roles. The career advancement framework for nurse educators is outlined in KMK No. 40 of 2017, but it remains largely conceptual and lacks specific guidelines. The ratio of nurse educators to students in hospitals varies significantly. For example, preceptorship programs typically maintain a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio. In clinical mentorship models, a 1:1 ratio is common, while facility-based mentoring can range from 1:6 to 1:8.(30) Research at Sanglah Hospital reveals that out of 1,500 employed nurses, only 10 are designated as educators.(21) This disparity raises concerns among nurse managers about the effectiveness of clinical education. Additionally, management support in providing rewards is a critical factor influencing nurse educators. While nurse educators receive rewards as part of their additional clinical responsibilities, the specifics of these rewards in Indonesia remain ambiguous.(21) In contrast, nurse educators in the United Kingdom earn an annual salary of £40,736 (approximately Rp. 667,635,74) (Ryder, 2023), while those in the United States receive about $82,000 (approximately Rp. 1,259,278,100).(31) This disparity in compensation can significantly affect the competency of nurse educators in fulfilling their roles.

Student Mentoring Programs Managed by Higher Education Institutions

According to accreditation standards, college students engaged in clinical practice within healthcare settings must be supervised by a clinical mentor from the hospital.(32) Higher education institutions play a vital role in enhancing the competencies of nurse educators. These educators provide essential support within healthcare education. Clinically competent and skilled nurse educators are considered crucial assets in professional development. They are expected to offer mentoring, conduct evaluations, and serve as role models for clinical skills in patient care.(33) Development programs for nurse educators continue to evolve in tandem with advancements in clinical education within hospitals, with support from higher education institutions.

Lack of Definition for Nurse Educators and Career Advancement

The definitions and career advancement pathways for nurse educators in Indonesia remain ambiguous. Nurse educators are commonly referred to as preceptors, clinical instructors, and mentors. A preceptor is a nurse educator who facilitates orientation to boost student motivation and address competency gaps.(34) In contrast, a mentor is a nurse educator who fosters learning through professional relationships between experienced and novice nurses.(35) In Singapore, clinical instructors are responsible for managing student mentoring programs.(36)

Nurse managers play a vital role in enhancing the competencies of nurse educators. Research indicates that many nurse managers lack strategic plans for professional development within their wards, often concentrating solely on the individual needs of nurses during training activities.(2) Nevertheless, nurse managers are expected to possess skills in managing personnel, organizational resources, and change.(18)

Moreover, nurse managers have raised concerns about the lack of clarity in the regulatory framework governing the career advancement of nurse educators. In Indonesia, PMK No. 40 of 2017 recognizes the role of nurse educators, but the regulation fails to formally define their roles, responsibilities, competencies, or career pathways. Currently, nurse educators primarily focus on supervising students, yet an analysis of the career advancement framework indicates that they also play a significant role in educating nurses.(37)

CONCLUSIONS

This study concludes that nurse managers, as the individuals responsible for the nurse educator program, have unique insights into managing nurse educators in hospitals. The research identified six themes, encompassing 18 subthemes and 55 categories. Recommendations from this study emphasize the need for nurse managers to prioritize the professional development and competencies of nurse educators in hospital settings. Additionally, it is recommended that the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education and Culture consider the career progression of nurse educators within hospitals. By establishing clearer competencies for nurse educators, it is expected that they will gain greater confidence in their educational roles within healthcare settings.

REFERENCES

1. Poortaghi S, Shahmari M, Ghobadi A. Exploring nursing managers’ perceptions of nursing workforce management during the outbreak of COVID-19: a content analysis study. BMC Nurs. 2021 Dec 1;20(1).

2. Lammintakanen J, Kivinen T, Kinnunen J. Human resource development in nursing: Views of nurse managers and nursing staff. J Nurs Manag. 2008 Jul;16(5):556–64.

3. Druse FC, Foradori MA, Hatzfeld JJ. Research interest groups: Creating the foundation for professional nursing education, mentorship, and collaboration. Nurs Outlook. 2022;70(6, Supplement 2):S146–52.

4. Situmorang R. Pengalaman clinical instructor dalam proses pembelajaran praktik mahasiswa keperawatan. 2022

5. Ramani S, Leinster S. AMEE guide no. 34: Teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2008;30(4):347–64.

6. Spencer J. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine learning and teaching in the clinical environment. 2003.

7. Skaria R, Montayre J. Cultural intelligence and intercultural effectiveness among nurse educators: A mixed-method study. Nurse Educ Today. 2023 Feb 1;121.

8. Zuck E. Effect of Mentorship on New Graduate Nurses’ Assertive Communication: An Evidence Review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(SUPPL 5).

9. Quinlan-Colwell A. A Verbal Scrapbook Tribute to Ellyn Schreiner-Friend, Nurse, Mentor, Leader. Pain Manag Nurs [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Sep 26];21(5):399–400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2020.07.005

10. L’Ecuyer KM, Hyde MJ, Shatto BJ. Preceptors’ perception of role competency. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2018 May 1;49(5):233–40.

11. Nuryani SNA, Arnyana IBP, Parwati NN, Dantes GR, Juanamasta IG. Benefits and Challenges of Clinical Nurse Educator Roles: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2022 Jan 1;10:38–44.

12. Alghamdi R, Albloushi M, Alzahrani E, Aldawsari A, Alyousef S. Nursing Education Challenges from Saudi Nurse Educators’ and Leaders’ Perspectives: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2019 Feb 25;16(1).

13. Thornton K. Australian hospital-based nurse educators‘ perceptions of their role. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2018 Jun 1;49(6):274–81.

14. Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. California: SAGE Publisher; 2013.

15. Afiyanti Rachmawati. Metodologi penelitian kualitatif dalam riset keperawatan. Depok: PT. Rajagrafindo Persada.; 2014.

16. Polit,F.D & Beck T. Nursing research: Principles and methodes. Philadelphia: Lippincott.; 2010.

17. Rizany I, Handiyani H, Pujasari H, Erwandi D, Ika Wulandari C. Shift nurse in implementing shift work schedules and fatigue: A phenomenological study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1;4.

18. Mccallin AM, Frankson C. The role of the charge nurse manager: A descriptive exploratory study. J Nurs Manag. 2010 Apr;18(3):319–25.

19. Agusnita R, Hartono B, Hamid A, Ismainar H, Lita L. Analisis Peran Komite Keperawatan dalam Implementasi Kredensial Tenaga Keperawatan di RSUD Kota Dumai. Jurnal Ilmiah Universitas Batanghari Jambi. 2022 Oct 31;22(3):1768.

20. Jeffery J, Rogers S, Redley B, Searby A. Nurse manager support of graduate nurse development of work readiness: An integrative review. Vol. 32, Journal of Clinical Nursing. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2023. p. 5712–36.

21. Nuryani SNA, Arnyana IBP, Parwati NN, Dantes GR, Juanamasta IG. Benefits and challenges of clinical nurse educator roles: A qualitative exploratory study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2022 Jan 1;10:38–44.

22. Alghamdi R, Albloushi M, Alzahrani E, Aldawsari A, Alyousef S. Nursing education challenges from saudi nurse educators and leaders perspectives: A qualitative descriptive study. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2019 Feb 25;16(1).

23. Numminen O, Leino-Kilpi H, Isoaho H, Meretoja R. Congruence between nurse managers’ and nurses’ competence assessments: A correlation study. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2014 Nov 16;5(1).

24. McAllister M, Flynn T. The Capabilities of Nurse Educators (CONE) questionnaire: Development and evaluation. Nurse Educ Today. 2016 Apr 1;39:122–7.

25. Abou Zeid MAG, El-Ashry AM, Kamal MA, Khedr MA. Spiritual leadership among nursing educators: a correlational cross-sectional study with psychological capital. BMC Nurs. 2022 Dec 1;21(1).

26. Wulandari CI, Hariyati RTS, Handiyani H, Rizany I, Soemantri D, Novieastari E. Determinan Kepemimpinan Perawat Sebagai Pendidik di Pelayanan Kesehatan: Systematic Review. Jurnal Kedokteran Meditek. 2023 Oct 17;29(3):267–74.

27. Sobers-Butler K. Text or Not to Text? A Narrative Review of Texting as a Case Management Intervention. Prof Case Manag [Internet]. 2021;26(5):250–4. Available from: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L635909264&from=export

28. Bourne MJ, Smeltzer SC, Kelly MM. Clinical teacher self-efficacy: A concept analysis. Vol. 52, Nurse Education in Practice. Elsevier Ltd; 2021.

29. Garner SL, Killingsworth E, Bradshaw M, Raj L, Johnson SR, Abijah SP, et al. The impact of simulation education on self-efficacy towards teaching for nurse educators. Int Nurs Rev. 2018 Dec 1;65(4):586–95.

30. Gcawu SN, van Rooyen D. Clinical teaching practices of nurse educators: An integrative literature review. Vol. 27, Health SA Gesondheid. AOSIS OpenJournals Publishing AOSIS (Pty) Ltd; 2022.

31. WGU. How do you become a clinical nurse educator? [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 9].

32. Badan Akreditasi Nasional Perguruan Tinggi (BAN PT). Peraturan Badan Akreditasi Nasional Perguruan Tinggi tentang Instrumen Akreditasi Program Studi. Jakarta; 2019.

33. Hankemeier DA, Kirby JL, Walker SE, Thrasher AB. Athletic Training Preceptors’ Perceived Learning Needs Regarding Preceptor Development. Athletic Training Education Journal. 2017 Jan 1;12(1):39–45.

34. Gholizadeh L, Shahbazi S, Valizadeh S, Mohammadzad M, Ghahramanian A, Shohani M. Nurse preceptors’ perceptions of benefits, rewards, support, and commitment to the preceptor role in a new preceptorship program. BMC Med Educ. 2022 Dec 1;22(1).

35. Arnold E; BK. Interpersonal Relationships: Professional Communication Skills for Nurses. 2011.

36. Lovecchio CP, DiMattio MJK, Hudacek S. Clinical liaison nurse model in a community hospital: A unique academic-practice partnership that strengthens clinical nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2012;51(11):609–15.

37. Kemenkes. Pengembangan jenjang karir profesional perawat klinis. 2017;1–72.

FINANCING

Thanks are conveyed to support by LPDP and BPPT Kemendikbudristek for providing funding for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Cicilia Ika Wulandari, Hanny Handiyani, Enie Novieastari, Diantha Soemantri.

Data curation: Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Formal analysis: Cicilia Ika Wulandari, Hanny Handiyani.

Acquisition of funds: Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Research: Cicilia Ika Wulandari, Hanny Handiyani, Enie Novieastari, Diantha Soemantri.

Methodology: Cicilia Ika Wulandari, Hanny Handiyani, Enie Novieastari, Diantha Soemantri.

Project management: Ichsan Rizany, Hanny Handiyani, Enie Novieastari, Diantha Soemantri.

Resources: Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Software: Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Supervision: Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Validation: Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Display: Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Drafting - original draft: Ichsan Rizany, Cicilia Ika Wulandari.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Ichsan Rizany.